Trip Report:

Volunteer Leader: Mark Hougardy | Organization: Eugene-based Hiking Club | Dates: September 10, 2017, | Participants: 7 | Type: Day hike and wayfinding

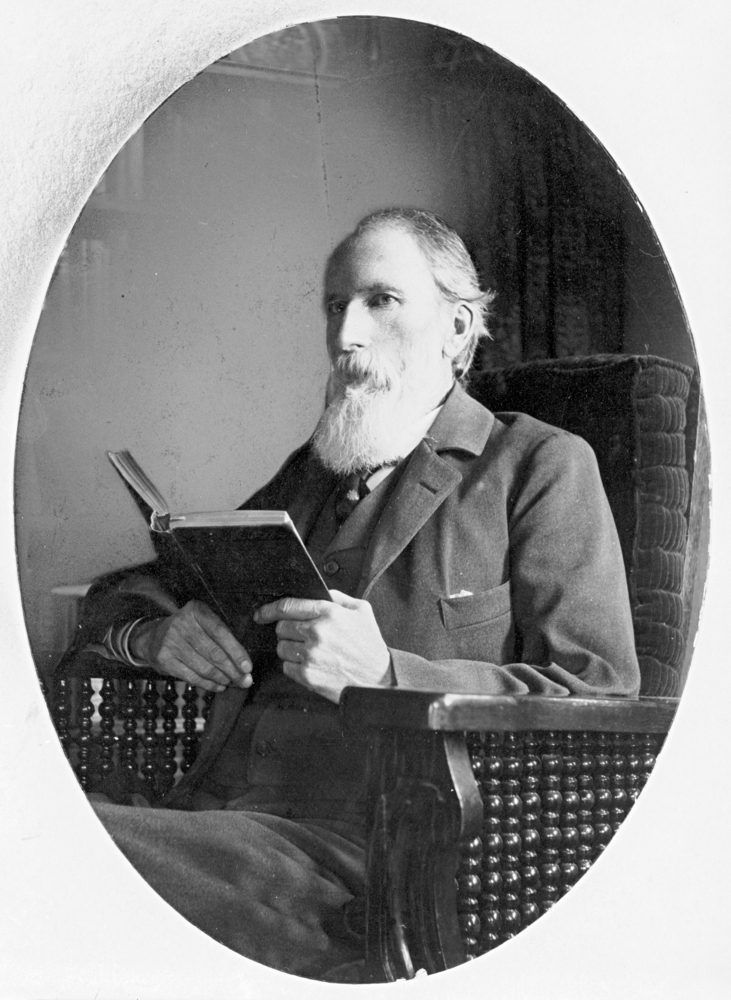

Along the forested backbone of Oregon’s Cascade Range is a large tranquil lake that invites “Where’s Waldo?” jokes. But, laughter aside, Waldo Lake is quiet. For those exploring the hushed shoreline, they might wander upon an old mountain hemlock blazed with the 130-year-old text, “Camp Edith, Waldo Lake.” At first, the blaze appears as an act of modern vandalism, but looking closer at the aged wood a modest story slowly reveals itself. The story is about a child who grew up to become the astute and reserved white-bearded grandfather of Oregon’s public lands. It was his passion that laid the groundwork for six national forests, over a dozen wilderness areas, and even support for Crater Lake National Park. Yet, most who visit these places today, don’t know this man’s name, Judge John Breckenridge Waldo. The few who know his name compare him to Emerson or Thoreau; some even call him “Oregon’s John Muir.”

The lake is rare in that it is a gas-free zone, only wind and human-powered boats are allowed.

My curiosity about John B. Waldo was piqued when I learned that his documents could be found nearby at the University of Oregon Special Collections archive. A visit to the archives was arranged through a local hiking club and several others joined me. A library staff member delivered several old boxes to our table.

As we carefully reviewed this man’s life, a grainy black-and-white photograph caught my gaze. The photo was etched with the text, “Camp Edith, Waldo Lake.” The picture was dated 1890 and revealed a couple of trees and a canoe. At first, I was stunned by the fortitude and strength involved in hauling early camera equipment and a canoe more than 70 miles or so into the mountains.

Then I was curious because none of my fellow hikers had ever heard of this place. I looked at modern maps, but there was no reference to Camp Edith. I looked at maps from the late 1800s and early 1900s, but still found nothing. The more I researched, the deeper the mystery became. This “lost” campsite of Waldo’s was a loose thread in a story, and I just had to pull at it.

John B. Waldo was born in 1844 to parents who had arrived just a year earlier on a wagon train and were new arrivals to the Willamette Valley. Waldo, as a child, had asthma which worsened in the summer as the valley filled with heat and smoke. Seeking refuge, Waldo and his brother made forays into the nearby Cascade Mountains for clean air. Waldo returned often.

As a young man, he studied law, became an attorney, and was eventually elected to the Oregon Supreme Court, even serving as a representative in the state legislature. He loved law and policy but always returned to the mountains, often for months at a time, to write about nature.

From 1877 to 1907, Waldo extensively explored and chronicled —in his words— the “untrammeled nature” of Oregon’s Cascades. He believed that modern life had “narrowing tendencies” on a person and that wilderness allowed difficulties to “be perceived and corrected, and the spirit enlarged and strengthened.”

He had seen the effects of over logging back east and overgrazing in the Cascades by sheep. Waldo imagined a protected place in the mountains where people could escape the toils of life. An individual’s trip would be assisted by an interconnected trail system dotted with lodges. These lodges would be roughly a day’s walk apart, where hikers and travelers could stay, enjoy a meal, and rest. Upon returning from his expeditions, he quietly and diligently advanced such a vision: a 40-mile-wide protected band along Oregon’s mountainous crest stretching 300 miles from the Columbia Gorge to the California border. Waldo spent decades and countless hours increasing public awareness through letter writing, newspaper posts, and using his professional resources to advocate for this vision.

Waldo died in 1907 at the age of 63; he had become ill while attempting to summit Mount Jefferson. His colleagues returned Waldo to his family farm outside of Salem, where he passed. After his death, his writings became missing, but Waldo had started something in the minds of others. In the following years, national forests and wilderness areas began to form a patchwork along Oregon’s crest. Outdoor enthusiasts created clubs like the Mazamas, the Chemeketans, and the Obsidians, all dedicated to experiencing the outdoors. Three of the west’s greatest national park lodges were constructed in Oregon: the Chateau at the Oregon Caves, Crater Lake Lodge, and the crowning gem Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood. Rangers opened campgrounds, trail maintenance volunteers began creating and maintaining hundreds of recreation trails, skiing enthusiasts opened ski resorts, and rafters opened rafting companies. Friends of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) worked to span Oregon with this narrow ribbon of trail that crosses the U.S. from Mexico to Canada. In the past few years, via a citizens’ initiative, Oregon voters secured funding so all fifth or sixth-grade students can move from their school classrooms into the outdoors to learn and be immersed in nature.

For almost 80 years, the location of Waldo’s writings and photos was unknown and thought to be lost. In the 1980s, these items were located in an attic and delivered to a conservation organization in Eugene. Eventually, his papers made their way to the University of Oregon archives and can be viewed today by appointment. It was here where I first saw the old grainy photo inscribed, “Camp Edith, Waldo Lake.” Supposedly this was one of his favorite locations. Yet, where was this place?

During the past year, I have been reading, researching, and trying to figure out where Camp Edith might be. I poured over maps, performed internet searches, and reviewed old hiking books but found nothing. I checked with living knowledge keepers: the seasoned hikers, campers, and old-timers in central Oregon. Most only knew about Waldo because of the lake that shares his name. Of the few who knew about Waldo as a preservationist, only a handful had heard about Camp Edith.

A man said he knew of the camp. He suggested that I look at Waldo’s obituary for guidance. One portion stood out. It read, “To him, the mountains with their purpling canyons and glittering snow peaks were a book to which there was no end. The beauty of the hills was a sermon.” Inspiring words, but was I any closer to finding Camp Edith?

Another person, a retired employee of the Forest Service, revealed she knew of the camp’s location. She added, “It’s easy to forget where a single tree is in the forest, but [she] could point me in the right direction if I wished.” Several weeks later, a PDF copy of Waldo’s transcribed 500-page diary arrived in my inbox from someone I never met along with the text, “A former colleague thought you might appreciate this.”

One individual, with ties to the Waldo documents, said he knew where the campsite was located, but, “It’s yours to find.”

Finally, I met an aged man who loved long-distance hiking and somehow knew that I had been looking for Camp Edith. He claimed to have walked across the U.S. a total of four times in his life and was eagerly looking forward to at least another two trips. He wore a Grateful Dead t-shirt and on his pack a bright yellow button of the Gadsden flag with a rattlesnake and the words, “Don’t Tread On Me.” The man said he had “hiked all over Oregon including Waldo Lake” and had seen the Camp Edith tree and knew the location. He had enjoyed eating a sandwich there. I leaned in, hoping for a quick answer to the location, but he uttered these enigmatic words, “When you find the tree, man, you’ll be there.” I left feeling none the wiser, or did I?

That winter, when skies in the Pacific Northwest are overcast and darkness comes quickly in the afternoon hours, I wrapped myself in a warm quilt. I jumped into reading Waldo’s 500-page diary. It was here that I learned that during Waldo’s treks, he traveled for months to nourish his insatiable wanderlust and love of the mountains. This included trekking as far south as California’s Mount Shasta.

But like many of us who desire to travel, when we do so, we become homesick for loved ones, and Waldo was no exception. In 1889, or thereabouts, to lessen his loneliness he christened a favorite camping site in honor of his daughter, Edith. Shortly after, a colleague blazed a heart-shape and Edith’s name into a tree trunk.

As I waited for the snow in the mountains to melt and for the highway to Waldo Lake to reopen, I casually picked up the old photo of Camp Edith that I had looked at a hundred times before and saw something small. I grabbed a magnifying glass. At that moment, I knew the basic location of the camp. I had enjoyed my journey up to this point, but now, others needed to share in the experience. Therefore, I enlisted members of the same hiking group I had met at the archives the year before.

Several months later, we arrived at the lake. I provisioned them with three items: a copy of the Camp Edith photo from 1890, a few telling diary entries from Waldo’s writings, and pointed them in a direction. Everyone was eager, if a bit perplexed, as we walked into the vast forest to find a single tree.

Waldo Lake is always an inspiring place to visit. It is one of the largest natural lakes in Oregon, roughly 5 miles in length and 2 miles in width. The waters are clear and turquoise and the deeper areas are bespeckled with shades of rich blue. Light can easily penetrate 60 feet deep and possibly further.

Progress was slow as we carefully crossed marshy fields, scrambled over downed logs, and occasionally got our feet muddy as they identified clues in the photo. The day was getting late and several questioned if the tree even existed. I was also beginning to wonder, as this was taking longer than expected, but then a joyous shout.

Arriving at the tree, we saw thirteen decades of bark growth had covered the blaze, but the inscription was still legible: “Camp Edith, Waldo Lake.”

After a year of reading Waldo’s papers, speaking with others, and carefully studying an old photo from 1890, my fellow explorers and I stood at Waldo’s lost campsite. Well, “lost” is a relative term. While we celebrated our discovery, we were not the first to locate the tree. People had likely visited here many centuries before Waldo’s time, and in more recent years pitched tents, or stopped for lunch along a lake’s edge, or even tried to solve the mystery of Camp Edith’s location for themselves.

Standing there, I remembered blissfully walking past this location several years earlier during a day hike, yet never turning to see the blaze on the tree. I shook my head at the wondrous absurdity of my journey, a year of research only to discover a place in the outdoors where I had walked before.

Sharing that moment with others, standing on the shore of a picturesque lake in the middle of the woods, was a sense of nourishment, renewal, and connection. The tree’s inscription shares a nearly forgotten story, but to me, this is not a monument. Waldo’s monument isn’t this inscription, or a lake with his name, or even dusty photos in an archive. Waldo’s monument —his legacy— is about generations of people being outside, connecting with nature, and enjoying Oregon’s beautiful mountains.

“The lake stretches away up to the North; crags and peaks tower above us. It is a splendid scene – this source of rivers and cities, hid away, like pure trains of thought from vulgar observation – in the deep bosom of the wilderness buried. Camp Edith sends you greeting, “greeting to Edith from ‘Papa’s Lake.’”

-An excerpt from one of Waldo’s 1890 letters

“Children born and reared here might be expected to have something of the wild flavor of nature in their composition.”

-Some of the last known words recorded in Waldo’s wilderness diary (between Aug 14- 17, 1907 just before his death)

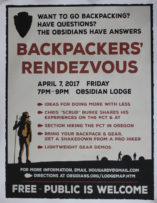

Volunteer Organizer: Mark Hougardy | Location: Eugene-based Hiking Group Lodge | Date: April 2017 | Duration: 1 day | Participants: 80+ | Type: Outreach Event

Volunteer Organizer: Mark Hougardy | Location: Eugene-based Hiking Group Lodge | Date: April 2017 | Duration: 1 day | Participants: 80+ | Type: Outreach Event

That’s me with the apple. The lodge’s owners Hal and Tonia quickly welcomed us as we arrived at their retreat/garden/camp in the woods. Hal offered us delicious Honey Crisp apples directly off the tree to enjoy on our hike. [Photo by Darko]

That’s me with the apple. The lodge’s owners Hal and Tonia quickly welcomed us as we arrived at their retreat/garden/camp in the woods. Hal offered us delicious Honey Crisp apples directly off the tree to enjoy on our hike. [Photo by Darko] Our 8-mile hike started up a reclaimed forest road, past cedar trees used by mountain lions for scratching, across the deep ravine where a rope was needed (shown), and finally to a deceptively steep forest road.

Our 8-mile hike started up a reclaimed forest road, past cedar trees used by mountain lions for scratching, across the deep ravine where a rope was needed (shown), and finally to a deceptively steep forest road. After a good heart-pounding climb, we arrived at the “Secret Spot,†the highest location within the Coast Range in Lane County. We had climbed roughly 1,600 feet from where we started but the view made up for it. Looking east we could see 130+ miles in the distance: in the north, Mt Hood, followed by Mt, Jefferson, Three-Fingered Jack, North, Middle and South Sister, Mt. Bachelor, and finally 125 miles further south, Diamond Peak.

After a good heart-pounding climb, we arrived at the “Secret Spot,†the highest location within the Coast Range in Lane County. We had climbed roughly 1,600 feet from where we started but the view made up for it. Looking east we could see 130+ miles in the distance: in the north, Mt Hood, followed by Mt, Jefferson, Three-Fingered Jack, North, Middle and South Sister, Mt. Bachelor, and finally 125 miles further south, Diamond Peak. We rested, enjoyed some lunch, and then traversed back down the forest road to several turnoffs, and a forest trail that deposited us back at Big Bear. That evening we shared a potluck with neighbors; everyone’s gardens were abundant and we and enjoyed the bounty of harvest-time meals. Later that evening we enjoyed guitar folk music by the fire and enjoyed freshly picked grapes (shown below). In the morning we hung out, explored the local creek, enjoyed the garden, and planned a route for a 42-mile, 4-day backpacking trip to the coast for next spring.

We rested, enjoyed some lunch, and then traversed back down the forest road to several turnoffs, and a forest trail that deposited us back at Big Bear. That evening we shared a potluck with neighbors; everyone’s gardens were abundant and we and enjoyed the bounty of harvest-time meals. Later that evening we enjoyed guitar folk music by the fire and enjoyed freshly picked grapes (shown below). In the morning we hung out, explored the local creek, enjoyed the garden, and planned a route for a 42-mile, 4-day backpacking trip to the coast for next spring.

A view of the Santiam Pass trailhead, mile number 2006.9 on the PCT. As my wife and I gathered our gear, we met two sixty-something ladies that started at Crater Lake for a section hike several weeks earlier. These women had already hiked about 175 miles.

A view of the Santiam Pass trailhead, mile number 2006.9 on the PCT. As my wife and I gathered our gear, we met two sixty-something ladies that started at Crater Lake for a section hike several weeks earlier. These women had already hiked about 175 miles. The weather was beautiful – if a bit warm – that morning. We were joined by two friends, Jack and Cindy, who drove us to the trailhead and then hiked with us for the first five miles of our journey.

The weather was beautiful – if a bit warm – that morning. We were joined by two friends, Jack and Cindy, who drove us to the trailhead and then hiked with us for the first five miles of our journey. A view of the north side of Three Fingered Jack, a jagged and rugged mountain in the High Cascades that has banded stripes. A PCT thru-hiker stands in the foreground. He was one of about 25 who passed us that day; the oldest being somewhere in her 60s, the youngest about 18, and about half of the thru-hikers were female.

A view of the north side of Three Fingered Jack, a jagged and rugged mountain in the High Cascades that has banded stripes. A PCT thru-hiker stands in the foreground. He was one of about 25 who passed us that day; the oldest being somewhere in her 60s, the youngest about 18, and about half of the thru-hikers were female. A view of Wasco Lake the following morning at about 7 am.

A view of Wasco Lake the following morning at about 7 am. We enjoyed a mid-morning break on the shores of Rockpile Lake. Several thru-hikers can be seen on the trail at the left. The two women we met a day earlier enjoyed their lunch and a quick swim on the opposite side of the lake.

We enjoyed a mid-morning break on the shores of Rockpile Lake. Several thru-hikers can be seen on the trail at the left. The two women we met a day earlier enjoyed their lunch and a quick swim on the opposite side of the lake. Much of our day was spent walking through woods that had been burned several years earlier and were now recovering. In the distance, the peak of Mount Jefferson made frequent and teasing appearances.

Much of our day was spent walking through woods that had been burned several years earlier and were now recovering. In the distance, the peak of Mount Jefferson made frequent and teasing appearances. That evening we camped at Shale Lake and enjoyed an amazing view of the south side of Mount Jefferson. We ate our dinner and watched the evening light blanket the slopes of this iconic High Cascades peak.

That evening we camped at Shale Lake and enjoyed an amazing view of the south side of Mount Jefferson. We ate our dinner and watched the evening light blanket the slopes of this iconic High Cascades peak. Looking upon a picturesque view of Pamelia Lake from the PCT. This area is a limited entry zone requiring a permit to camp. Our hike that morning was in the forest where we encountered some sizeable old growth trees, and at one point we rounded a corner and surprised a grouse.

Looking upon a picturesque view of Pamelia Lake from the PCT. This area is a limited entry zone requiring a permit to camp. Our hike that morning was in the forest where we encountered some sizeable old growth trees, and at one point we rounded a corner and surprised a grouse. Milk Creek has cut a 100-foot deep gorge into the slopes of Mount Jefferson. Several backpackers are seen crossing the creek below us.

Milk Creek has cut a 100-foot deep gorge into the slopes of Mount Jefferson. Several backpackers are seen crossing the creek below us. Overgrown and green, this is what the trail looked like for the rest of the afternoon. It was also humid and hot, making our progress slower than expected. Occasionally, we would see glimpses of Mount Jefferson through the trees.

Overgrown and green, this is what the trail looked like for the rest of the afternoon. It was also humid and hot, making our progress slower than expected. Occasionally, we would see glimpses of Mount Jefferson through the trees. Russell Creek pours off the mountainside where it meets a “flat†area for about 100 feet before dropping into a deep gorge; this more level area is where the trail crosses. Earlier in the season, the flow can be very strong and this can be a dangerous crossing. Today, though, it just brought about some wet shoes. In this image, a hiker approaches the crossing area. We spoke with her later to find out that she was 18 and was hiking 250 miles of the PCT by herself.

Russell Creek pours off the mountainside where it meets a “flat†area for about 100 feet before dropping into a deep gorge; this more level area is where the trail crosses. Earlier in the season, the flow can be very strong and this can be a dangerous crossing. Today, though, it just brought about some wet shoes. In this image, a hiker approaches the crossing area. We spoke with her later to find out that she was 18 and was hiking 250 miles of the PCT by herself. We enjoyed breakfast under this stunning skyline.

We enjoyed breakfast under this stunning skyline. The next morning we climbed 1,200 feet out of Jefferson Park. The views were magnificent: wildflowers were in bloom along the trail, and at times it was hard to hear because of the abundance of buzzing coming off nearby flowers.

The next morning we climbed 1,200 feet out of Jefferson Park. The views were magnificent: wildflowers were in bloom along the trail, and at times it was hard to hear because of the abundance of buzzing coming off nearby flowers. We reached the trail’s summit and could see Mount Hood in the distance. Descending the slope, we passed several snowfields. For several hours our progress was slow going because of the loose rocks, though the trail soon became forested and we passed a number of beautiful mountain lakes.

We reached the trail’s summit and could see Mount Hood in the distance. Descending the slope, we passed several snowfields. For several hours our progress was slow going because of the loose rocks, though the trail soon became forested and we passed a number of beautiful mountain lakes. Late in the afternoon, we reached Ollalie Lake. Here is a view looking south across the area we just hiked, and in the distance is Mount Jefferson. About two dozen thru-hikers were staying at Ollalie Lake to rest.

Late in the afternoon, we reached Ollalie Lake. Here is a view looking south across the area we just hiked, and in the distance is Mount Jefferson. About two dozen thru-hikers were staying at Ollalie Lake to rest. Ollalie Lake has a small store where my wife and I eagerly purchased a bag of sea salt and vinegar potato chips and promptly devoured the entire bag. At one point there were a whopping total of eight stinky hikers in that little store – ah, the aroma of humanity!

Ollalie Lake has a small store where my wife and I eagerly purchased a bag of sea salt and vinegar potato chips and promptly devoured the entire bag. At one point there were a whopping total of eight stinky hikers in that little store – ah, the aroma of humanity! The trail on day five was mostly flat and in the shade of tall trees, making trekking much easier. The forest was drier in this region and water was less abundant than before. When the opportunity presented itself, we filled up our bottles at a small, tranquil trailside spring. The temperature that day was especially warm.

The trail on day five was mostly flat and in the shade of tall trees, making trekking much easier. The forest was drier in this region and water was less abundant than before. When the opportunity presented itself, we filled up our bottles at a small, tranquil trailside spring. The temperature that day was especially warm. We arrived at Trooper Springs near the Lemiti Marsh area. This was our last water for about twelve miles. The spring was a welcome site although a small and precarious platform needed repair. We were attacked by horseflies; they were numerous, aggressive, and very persistent. Needless to say, we did not stay long.

We arrived at Trooper Springs near the Lemiti Marsh area. This was our last water for about twelve miles. The spring was a welcome site although a small and precarious platform needed repair. We were attacked by horseflies; they were numerous, aggressive, and very persistent. Needless to say, we did not stay long. Taking care of some much-needed laundry at the spring using the “Ziplock spin cycle” washing method.

Taking care of some much-needed laundry at the spring using the “Ziplock spin cycle” washing method. Walking through a clearcut was a stark contrast to the lush forest we had seen all day. Near this area, we found the strangest price of trash on the trip: a Howard Johnson’s hotel key card lying next to the trail. We picked it up.

Walking through a clearcut was a stark contrast to the lush forest we had seen all day. Near this area, we found the strangest price of trash on the trip: a Howard Johnson’s hotel key card lying next to the trail. We picked it up. We located a bare spot at the edge of the trail and camped for the night. Trailside camping can look messy, but everything goes back into the pack and we always leave the site cleaner than we found it.

We located a bare spot at the edge of the trail and camped for the night. Trailside camping can look messy, but everything goes back into the pack and we always leave the site cleaner than we found it. Shown is an old style PCT trail marker that we found, one of the few older versions that we saw on the entire trip.

Shown is an old style PCT trail marker that we found, one of the few older versions that we saw on the entire trip. Crossing the Warm Springs River. It was more a small creek at this point, but the water the clean and cold – a welcome site.

Crossing the Warm Springs River. It was more a small creek at this point, but the water the clean and cold – a welcome site. As I took off my shoes I realized just how dusty the trail was that day.

As I took off my shoes I realized just how dusty the trail was that day. That evening we stealth camped near the trail close to Timothy Lake. During the night we unzipped the tent for a “nature break” – only to be scolded by an owl that repeatedly whooo’d at us until we went back to bed.

That evening we stealth camped near the trail close to Timothy Lake. During the night we unzipped the tent for a “nature break” – only to be scolded by an owl that repeatedly whooo’d at us until we went back to bed. Several miles down the trail was Crater Creek, a beautiful riparian area with some astonishingly cold water: a welcome find on a hot day. We soaked our feet, took a twenty-second dip (the water was that frigid), then soaked our shirts and put them on as a natural air-conditioner. We made a stop at Little Crater Lake, the source of the creek. Little Crater Lake is astonishingly blue like it’s larger cousin, but this was not volcanic in origin. Rather, this was a large artesian well. Continuing down the trail, we passed a gravel forest service road and found a bag hanging on PCT post. Inside were some small apples or Asian pears – some unexpected trail magic in the middle of nowhere.

Several miles down the trail was Crater Creek, a beautiful riparian area with some astonishingly cold water: a welcome find on a hot day. We soaked our feet, took a twenty-second dip (the water was that frigid), then soaked our shirts and put them on as a natural air-conditioner. We made a stop at Little Crater Lake, the source of the creek. Little Crater Lake is astonishingly blue like it’s larger cousin, but this was not volcanic in origin. Rather, this was a large artesian well. Continuing down the trail, we passed a gravel forest service road and found a bag hanging on PCT post. Inside were some small apples or Asian pears – some unexpected trail magic in the middle of nowhere. This was our first view of Mount Hood after about 40 miles of hiking – what a fantastic sight.

This was our first view of Mount Hood after about 40 miles of hiking – what a fantastic sight. We took a side trail to Frog Lake for some water where there was a hand pump that drew water from a well. As we entered the campground we were momentary celebrities answering questions like: “Where did you hike from?†“How many days have you been out?†“Tell me about your gear?†etc. It was an odd but welcome feeling. That night, we camped just outside the campground on a forest road.

We took a side trail to Frog Lake for some water where there was a hand pump that drew water from a well. As we entered the campground we were momentary celebrities answering questions like: “Where did you hike from?†“How many days have you been out?†“Tell me about your gear?†etc. It was an odd but welcome feeling. That night, we camped just outside the campground on a forest road. Finally, the green of the trees turned to open space and vistas as we passed the timberline. It was windy with twenty to thirty mile an hour gusts that kicked up sand and dust. We wore our sunglasses to keep volcanic grit out of our eyes.

Finally, the green of the trees turned to open space and vistas as we passed the timberline. It was windy with twenty to thirty mile an hour gusts that kicked up sand and dust. We wore our sunglasses to keep volcanic grit out of our eyes. There was an abundance of mountain flowers on the trail.

There was an abundance of mountain flowers on the trail. Close to the Timberline Lodge, the views were fantastic! We could see much of the route that we had spent the past week traversing.

Close to the Timberline Lodge, the views were fantastic! We could see much of the route that we had spent the past week traversing. We arrived at the Timberline Lodge, mile 2107.3 on the PCT, and 100 miles from our starting point at Santiam Pass. Inside the lodge, scores of thru-hikers had taken refuge in the common areas. There was access to food and good company, with couches for sleeping and a warm fire to enjoy in the evening. We met some new friends here: Shepherd, Snow, Lonestar, and Patch, all thru-hikers who started at the Mexican border and were resting before their final push into Washington State and Canada.

We arrived at the Timberline Lodge, mile 2107.3 on the PCT, and 100 miles from our starting point at Santiam Pass. Inside the lodge, scores of thru-hikers had taken refuge in the common areas. There was access to food and good company, with couches for sleeping and a warm fire to enjoy in the evening. We met some new friends here: Shepherd, Snow, Lonestar, and Patch, all thru-hikers who started at the Mexican border and were resting before their final push into Washington State and Canada. Looking through the door at the Timberline Lodge onto the Roosevelt Terrace: in the distance Jefferson Peak, and behind it, Three Fingered Jack and Santiam Pass. From the lodge, we were able to take public transit back home.

Looking through the door at the Timberline Lodge onto the Roosevelt Terrace: in the distance Jefferson Peak, and behind it, Three Fingered Jack and Santiam Pass. From the lodge, we were able to take public transit back home. We parked at a junction and walked down an old logging road that was being reclaimed by the forest. Then we disappeared into the bushes, venturing down an elk trail. Posted on a tree was a sign that told us this was not the path to the Devil’s Staircase waterfall and unless you’re prepared to stay the night, and have Search and Rescue to look for you, to turn back. Fortunately, we had a guide for our inaugural visit.

We parked at a junction and walked down an old logging road that was being reclaimed by the forest. Then we disappeared into the bushes, venturing down an elk trail. Posted on a tree was a sign that told us this was not the path to the Devil’s Staircase waterfall and unless you’re prepared to stay the night, and have Search and Rescue to look for you, to turn back. Fortunately, we had a guide for our inaugural visit. A forest of Salmonberries obstructed our path, so we made a trail straight up a ridge, then down into a forest of sword ferns. The ferns stood at five to six feet in height, so they engulfed us all and many of the shorter members traveled with their arms raised straight overhead. These tranquil glens often hid downed logs and it was easy to twist ankles or slam shins.

A forest of Salmonberries obstructed our path, so we made a trail straight up a ridge, then down into a forest of sword ferns. The ferns stood at five to six feet in height, so they engulfed us all and many of the shorter members traveled with their arms raised straight overhead. These tranquil glens often hid downed logs and it was easy to twist ankles or slam shins. A fallen giant became our catwalk above the salmonberries, foxgloves, and ferns. We crossed a creek, but could barely see the water because of the thick undergrowth. Scampering down the side of the massive tree, we squatted and crawled through a small jungle, then emerged at the root base of the fallen giant – it was 25 feet tall!

A fallen giant became our catwalk above the salmonberries, foxgloves, and ferns. We crossed a creek, but could barely see the water because of the thick undergrowth. Scampering down the side of the massive tree, we squatted and crawled through a small jungle, then emerged at the root base of the fallen giant – it was 25 feet tall! In front of us was the Dark Grove, a cathedral of 8-foot wide Douglas Fir trees. The trees were dark in appearance, the result of fire about 150 years earlier. Touching the bark a charcoal residue was imprinted on fingers. The tree model is Becky Lipton.

In front of us was the Dark Grove, a cathedral of 8-foot wide Douglas Fir trees. The trees were dark in appearance, the result of fire about 150 years earlier. Touching the bark a charcoal residue was imprinted on fingers. The tree model is Becky Lipton. Crossing back across the fallen giant, we stood at the base of one of the largest trees we saw that day. Eight people stood at its base, arms outstretched and hands grasped. They counted one, two, three… their calls became muffled as they rounded the opposite side…the voices returned and the loop stopped – at seven and a half people! This immense tree was somewhere between 35 to 40 feet in circumference! Several hikers mentioned they felt like kids in a giant outdoor playground.

Crossing back across the fallen giant, we stood at the base of one of the largest trees we saw that day. Eight people stood at its base, arms outstretched and hands grasped. They counted one, two, three… their calls became muffled as they rounded the opposite side…the voices returned and the loop stopped – at seven and a half people! This immense tree was somewhere between 35 to 40 feet in circumference! Several hikers mentioned they felt like kids in a giant outdoor playground.

The Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon is breathtakingly beautiful. This diverse landscape of volcanoes, snow, forests, creeks, lava fields, and lakes gives hikers the opportunity to explore a vibrant topography. The wilderness encompasses 281,190-acres and is dominated by three volcanic peaks: North, Middle, and South, that each exceeds 10,000-feet in height! Several paved roads around the perimeter of the wilderness allow visitors to see vistas with just a car ride, but to really appreciate the immensity of this setting some footwork is required. Here are some pictures of a 34-mile, 4-day trip along the north and eastern portions of the wilderness ending between Middle and South Sister at a subalpine area known as Camp Lake.

The Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon is breathtakingly beautiful. This diverse landscape of volcanoes, snow, forests, creeks, lava fields, and lakes gives hikers the opportunity to explore a vibrant topography. The wilderness encompasses 281,190-acres and is dominated by three volcanic peaks: North, Middle, and South, that each exceeds 10,000-feet in height! Several paved roads around the perimeter of the wilderness allow visitors to see vistas with just a car ride, but to really appreciate the immensity of this setting some footwork is required. Here are some pictures of a 34-mile, 4-day trip along the north and eastern portions of the wilderness ending between Middle and South Sister at a subalpine area known as Camp Lake. My wife and I began our first day with a late start; we hiked 3 miles south from the Lava Camp trailhead and spent the night at South Matthieu Lake. Smoke from forest fires in the region made everything, even a view of North Sister and the moon, opaque. That night, an anticipated cool breeze was replaced by a warm wind that blew in from high plains of Oregon where a large ground fire was burning. In the middle of the night, the smoke became extremely thick and breathing for several hours was difficult. By morning the winds had shifted and the air was clearer.

My wife and I began our first day with a late start; we hiked 3 miles south from the Lava Camp trailhead and spent the night at South Matthieu Lake. Smoke from forest fires in the region made everything, even a view of North Sister and the moon, opaque. That night, an anticipated cool breeze was replaced by a warm wind that blew in from high plains of Oregon where a large ground fire was burning. In the middle of the night, the smoke became extremely thick and breathing for several hours was difficult. By morning the winds had shifted and the air was clearer. The next day we hiked 14 miles; 7 of which reminded us just how destructive forest fires can be, constantly around us were the stark and charcoaled remains of incinerated trees. This conflagration was called the Pole Creek Fire and occurred just 3 years ago in 2012.

The next day we hiked 14 miles; 7 of which reminded us just how destructive forest fires can be, constantly around us were the stark and charcoaled remains of incinerated trees. This conflagration was called the Pole Creek Fire and occurred just 3 years ago in 2012. Several small creeks crossed our path, most were dry, but Alder Creek’s water was cold and clear even though the flow was very low. The creek offered a respite from a temperature of 85 degrees and hot sun that was beating down. We welcomed the opportunity for rest and refill our water bottles at this little pool.

Several small creeks crossed our path, most were dry, but Alder Creek’s water was cold and clear even though the flow was very low. The creek offered a respite from a temperature of 85 degrees and hot sun that was beating down. We welcomed the opportunity for rest and refill our water bottles at this little pool. The North Sister towers in the distance. Continuing south the trail crossed several areas where the fire had not reached; these were often pumice expanses where vegetation was dispersed.

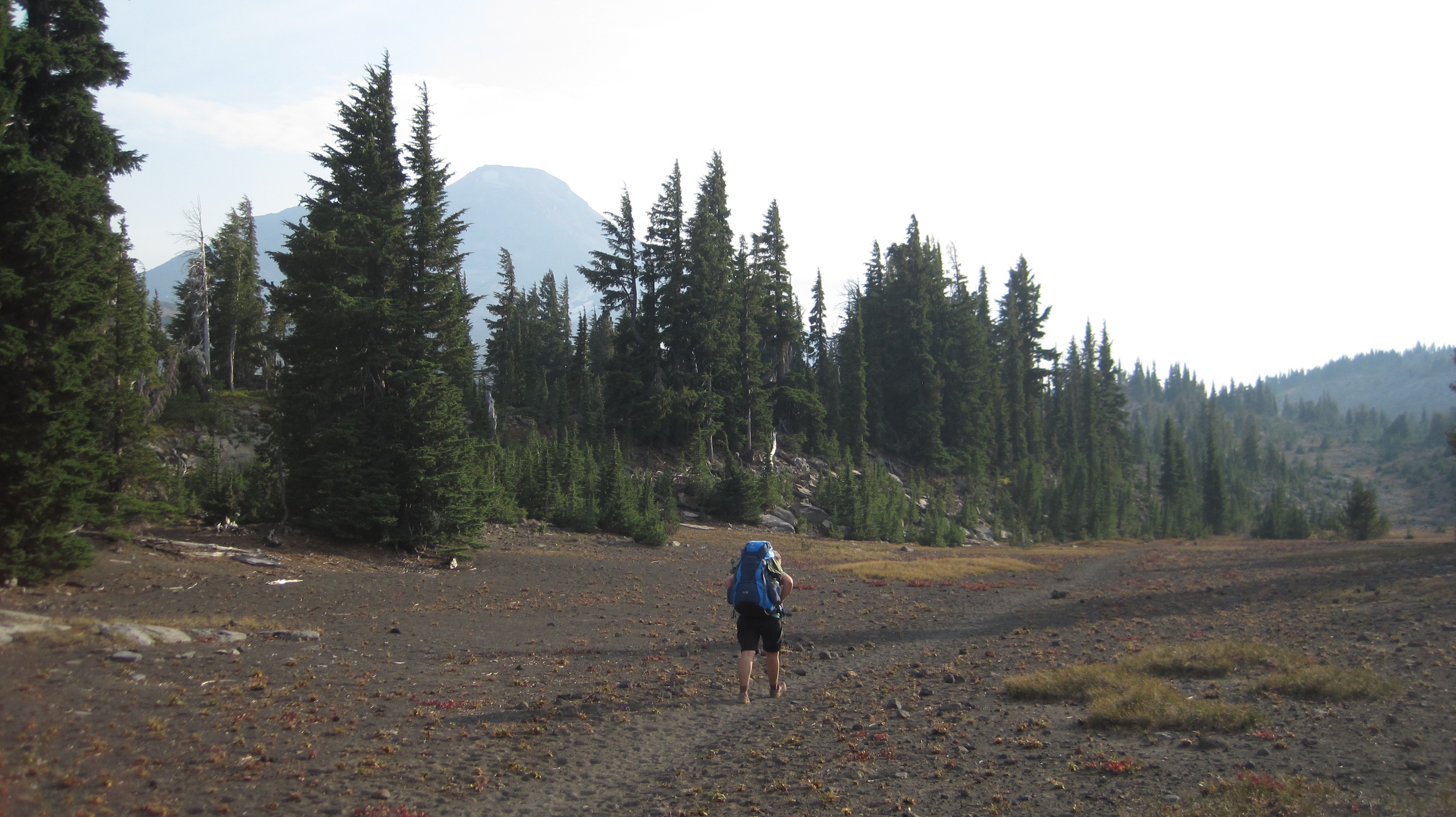

The North Sister towers in the distance. Continuing south the trail crossed several areas where the fire had not reached; these were often pumice expanses where vegetation was dispersed. As we crossed Soap Creek we saw a number Bumble Bees buzzing from one flower to another. Soap Creek gets its name from the soapy color of the water; this is because of the sediment that gets carried down in the glacial meltwater.

As we crossed Soap Creek we saw a number Bumble Bees buzzing from one flower to another. Soap Creek gets its name from the soapy color of the water; this is because of the sediment that gets carried down in the glacial meltwater. The trail turned to the west and the terrain gradually increased in elevation. After about an hour and a half we crossed the North Fork of Whychus Creek, which had to be traversed via several logs that served as a makeshift bridge, below us the grey and auburn glacial melt water loudly churned. Its source was about 2 miles upstream at the Hayden and Diller Glaciers. After crossing the views opened up.

The trail turned to the west and the terrain gradually increased in elevation. After about an hour and a half we crossed the North Fork of Whychus Creek, which had to be traversed via several logs that served as a makeshift bridge, below us the grey and auburn glacial melt water loudly churned. Its source was about 2 miles upstream at the Hayden and Diller Glaciers. After crossing the views opened up. A photo of Christiane hiking through a pumice area on our way to Camp Lake; walking on this material is akin to walking on dry sand.

A photo of Christiane hiking through a pumice area on our way to Camp Lake; walking on this material is akin to walking on dry sand. What a beautiful landscape!

What a beautiful landscape! A view of South Sister on the horizon; this dramatic peak is 10,358-feet in elevation!

A view of South Sister on the horizon; this dramatic peak is 10,358-feet in elevation! Our destination for the night, Camp Lake at 6,952-feet. The wind here can be unrelenting, this is because the lake’s location is sandwiched in a pass between Middle and South Sister. The wind was strong that afternoon so we found sanctuary behind a glacial moraine and set up camp.

Our destination for the night, Camp Lake at 6,952-feet. The wind here can be unrelenting, this is because the lake’s location is sandwiched in a pass between Middle and South Sister. The wind was strong that afternoon so we found sanctuary behind a glacial moraine and set up camp. Our original plan was to stay the night at Camp Lake and then in the morning continue over the pass. This would have included: hiking up a climber’s trail for an hour and up several hundred feet in elevation, crossing over a snowfield and down the western side of the mountain and to several remote lakes then overland another 3 miles to the Pacific Crest Trail. But, uncertain weather changed our plans. The forecast had called for a rainstorm along with high winds within the next 24 hours and we were hoping to make it over the pass before the rain. That evening dark clouds marched across the sky. As the sun disappeared under the horizon the temperature dropped well into the 40s and that night we heard several deep and rumbling crashes of thunder. The wind howled into the morning and for several hours we heard rain outside and at times our tent was pelted by ice.

Our original plan was to stay the night at Camp Lake and then in the morning continue over the pass. This would have included: hiking up a climber’s trail for an hour and up several hundred feet in elevation, crossing over a snowfield and down the western side of the mountain and to several remote lakes then overland another 3 miles to the Pacific Crest Trail. But, uncertain weather changed our plans. The forecast had called for a rainstorm along with high winds within the next 24 hours and we were hoping to make it over the pass before the rain. That evening dark clouds marched across the sky. As the sun disappeared under the horizon the temperature dropped well into the 40s and that night we heard several deep and rumbling crashes of thunder. The wind howled into the morning and for several hours we heard rain outside and at times our tent was pelted by ice. When we woke, the sky was grey in color but appeared mostly calm, though as I stepped out from behind the shelter of the moraine the wind almost knocked me over. I collected water at the lake and was surprised at how chilled I had become in just a few minutes; the wind was deceptively cold. Partially frozen raindrops fell sporadically. My wife and I made the decision to hold off crossing over the pass during this trip. We would return by the route we came.

When we woke, the sky was grey in color but appeared mostly calm, though as I stepped out from behind the shelter of the moraine the wind almost knocked me over. I collected water at the lake and was surprised at how chilled I had become in just a few minutes; the wind was deceptively cold. Partially frozen raindrops fell sporadically. My wife and I made the decision to hold off crossing over the pass during this trip. We would return by the route we came. The area’s starkness was beautiful. Several tents were dotted around the area, all of them, like the tent, is shown in the photo, was strategically placed behind natural wind brakes.

The area’s starkness was beautiful. Several tents were dotted around the area, all of them, like the tent, is shown in the photo, was strategically placed behind natural wind brakes. Our hike off the mountain was cold and occasionally it rained on us. At about noon the sun briefly came out, but this did not last long for the sky again turned dark and overcast. We hiked out of the burn zone and returned to the Matthieu Lakes area about dinnertime. That evening, the weather was peaceable, but about 7 pm the wind started up, by 8 pm it roared through camp with gusts reaching 40-50 miles an hour, by 9 pm the rain started. This continued into dawn. We slept comfortably in our tent.

Our hike off the mountain was cold and occasionally it rained on us. At about noon the sun briefly came out, but this did not last long for the sky again turned dark and overcast. We hiked out of the burn zone and returned to the Matthieu Lakes area about dinnertime. That evening, the weather was peaceable, but about 7 pm the wind started up, by 8 pm it roared through camp with gusts reaching 40-50 miles an hour, by 9 pm the rain started. This continued into dawn. We slept comfortably in our tent. The next morning was drippy and low clouds blew over the treetops. Later that morning we hiked out the last 3 miles. As we approached the Lava Camp trailhead the sky offered us some brief patches of blue. We ended our day with each other clinking together mugs of trail coffee in honor of a good trip.

The next morning was drippy and low clouds blew over the treetops. Later that morning we hiked out the last 3 miles. As we approached the Lava Camp trailhead the sky offered us some brief patches of blue. We ended our day with each other clinking together mugs of trail coffee in honor of a good trip.

Waldo Lake is one of Oregon’s largest bodies of water, though its lack of amenities such as convenience stores, resorts, and ban of motorized motors upon the water makes this destination easily overlooked. If you’re interested in a great overnight backpacking trip to try the Jim Weaver Loop, a 20.2-mile trail around Waldo lake, here are some photos taken in early July.

Waldo Lake is one of Oregon’s largest bodies of water, though its lack of amenities such as convenience stores, resorts, and ban of motorized motors upon the water makes this destination easily overlooked. If you’re interested in a great overnight backpacking trip to try the Jim Weaver Loop, a 20.2-mile trail around Waldo lake, here are some photos taken in early July. Near Mile 2. Our first stop was at the South Waldo shelter, it was fully equipped with wood and a stove; this is a popular destination in the winter. We continued on.

Near Mile 2. Our first stop was at the South Waldo shelter, it was fully equipped with wood and a stove; this is a popular destination in the winter. We continued on. The south shore had some great views of the South and Middle Sisters. The trail now meandered up the western side of the lake.

The south shore had some great views of the South and Middle Sisters. The trail now meandered up the western side of the lake. Cascade Blueberry

Cascade Blueberry Close to Mile 5. Overlooking the picturesque Klovdahl Bay. Overhead, the clouds began building into thunderheads; in the distance, we could hear the rumbling crescendo of thunder as though gigantic timpani drums were being struck.

Close to Mile 5. Overlooking the picturesque Klovdahl Bay. Overhead, the clouds began building into thunderheads; in the distance, we could hear the rumbling crescendo of thunder as though gigantic timpani drums were being struck. The western trail has a number of places where the forest looks like it had a close encounter with a forest fire; note the scoring on the tree at the right.

The western trail has a number of places where the forest looks like it had a close encounter with a forest fire; note the scoring on the tree at the right. Mile 10. Continuing north. Seen in the right on the image, about 2-miles away is a scarred hilltop within the burn zone.

Mile 10. Continuing north. Seen in the right on the image, about 2-miles away is a scarred hilltop within the burn zone. We spied several campsites peppered along the western shore of the lake, but as we reached the northern shore we discovered a favorite spot was vacant. As evening approached we appreciated a gentle breeze that chased most of the mosquitoes away.

We spied several campsites peppered along the western shore of the lake, but as we reached the northern shore we discovered a favorite spot was vacant. As evening approached we appreciated a gentle breeze that chased most of the mosquitoes away. Enjoying a gorgeous sunset. The sky was clear that night when the stars came out they were so bright you could almost touch them.

Enjoying a gorgeous sunset. The sky was clear that night when the stars came out they were so bright you could almost touch them. A very small toad had made its home just outside our tent during the night. It was discovered in the morning hiding next to one of our shoes.

A very small toad had made its home just outside our tent during the night. It was discovered in the morning hiding next to one of our shoes. Roughly Mile 12. Heading east, the trail meanders through the burn zone along the north shore. This day was going to be hot so we tried to cross before the sun rose too high in the sky. Several weeks earlier, during

Roughly Mile 12. Heading east, the trail meanders through the burn zone along the north shore. This day was going to be hot so we tried to cross before the sun rose too high in the sky. Several weeks earlier, during  Mile 13-ish. Standing on the north shore looking across to the southern shore. The morning was calm, it was difficult to tell where the sky ended and the lake began. Determining the depth of the logs seen the water was difficult, but if the terrain continued its steep angle into the water, these logs were at least 40 feet deep in the foreground and 60+ feet deep further out.

Mile 13-ish. Standing on the north shore looking across to the southern shore. The morning was calm, it was difficult to tell where the sky ended and the lake began. Determining the depth of the logs seen the water was difficult, but if the terrain continued its steep angle into the water, these logs were at least 40 feet deep in the foreground and 60+ feet deep further out. A Couple Selfie taken on the trail within the burn zone.

A Couple Selfie taken on the trail within the burn zone. We’re out of the burn zone and heading south along the eastern edge of the lake. Half of the trail around Waldo Lake is in the woods, with only brief glimpses of the water. Be prepared to see lots of trees.

We’re out of the burn zone and heading south along the eastern edge of the lake. Half of the trail around Waldo Lake is in the woods, with only brief glimpses of the water. Be prepared to see lots of trees. Just as we neared the south shore a massive toad was seen at the edge of the trail eating mosquitoes. During the entire trip, mosquitoes were not a big issue, though the last several miles of the trail we were devoured by these little flying beasts! I was glad to see this toad!

Just as we neared the south shore a massive toad was seen at the edge of the trail eating mosquitoes. During the entire trip, mosquitoes were not a big issue, though the last several miles of the trail we were devoured by these little flying beasts! I was glad to see this toad! Mile 20.2. The best part of finishing the loop trail around Waldo Lake is that you can dip your feet into the lake’s cold and clean water.

Mile 20.2. The best part of finishing the loop trail around Waldo Lake is that you can dip your feet into the lake’s cold and clean water.

Approaching Wizard Island, even several miles away, is very impressive.

Approaching Wizard Island, even several miles away, is very impressive. As the boat approaches Wizard Island the size and grandeur of this volcanic cone become apparent.

As the boat approaches Wizard Island the size and grandeur of this volcanic cone become apparent. Hiking to the top of Wizard Island the trail climbs 760 feet, but this is nothing compared to the eastern rim of the crater which towers above me. In the photo, the Watchman scrapes the sky at 1840 feet above the lake’s surface. Seen between the trees, on the water (crossing Skell Channel) is a small white line, this is one of the boats that transport passengers to the island.

Hiking to the top of Wizard Island the trail climbs 760 feet, but this is nothing compared to the eastern rim of the crater which towers above me. In the photo, the Watchman scrapes the sky at 1840 feet above the lake’s surface. Seen between the trees, on the water (crossing Skell Channel) is a small white line, this is one of the boats that transport passengers to the island. The views hiking to the top of Wizard Island are jaw-dropping.

The views hiking to the top of Wizard Island are jaw-dropping. Think of Wizard Island as a small volcano, and it has a crater; this picture shows several people hiking out. The rim of Crater Lake looms on the horizon.

Think of Wizard Island as a small volcano, and it has a crater; this picture shows several people hiking out. The rim of Crater Lake looms on the horizon. This Ground Squirrel is a resident of Wizard Island. He was demanding a food tithe from me for visiting his island retreat.

This Ground Squirrel is a resident of Wizard Island. He was demanding a food tithe from me for visiting his island retreat. A view from atop Wizard Island looking across Crater Lake to the opposite rim which is about 5 miles away. The blue color is just magnificent.

A view from atop Wizard Island looking across Crater Lake to the opposite rim which is about 5 miles away. The blue color is just magnificent. Hiking down the cinder cone we enjoy a rich tapestry of colors – a masterpiece painted by nature!

Hiking down the cinder cone we enjoy a rich tapestry of colors – a masterpiece painted by nature! This is one of the few boats allowed on Crater Lake. It is seen here delivering visitors; this boat will take us on our return trip around the lake’s perimeter in a counterclockwise direction. Our next stop was the southern shore to see a slide area and the Phantom Ship.

This is one of the few boats allowed on Crater Lake. It is seen here delivering visitors; this boat will take us on our return trip around the lake’s perimeter in a counterclockwise direction. Our next stop was the southern shore to see a slide area and the Phantom Ship. The spires of the Phantom Ship, an island in the lake, which under low-light conditions resembles a ghost ship.

The spires of the Phantom Ship, an island in the lake, which under low-light conditions resembles a ghost ship. Looking into the water from the edge of the boat we saw this dramatic difference in color. The interpreter on the boat said the contrast was because we were passing over an underwater ledge, to the left the water depth was about 900 feet, to the right the depths plunged to 1,600 feet!

Looking into the water from the edge of the boat we saw this dramatic difference in color. The interpreter on the boat said the contrast was because we were passing over an underwater ledge, to the left the water depth was about 900 feet, to the right the depths plunged to 1,600 feet! Crater Lake’s legendary “blue” water.

Crater Lake’s legendary “blue” water.