Few symbols represent the spirit of the American West like wild Bison grazing on the expansive and open prairie.

There is something about this setting that makes the heart pump a little faster and one’s breathing to quicken. Such a setting whispers about the time when our ancestors lived here, or even migrated across this expansive landscape. It quietly reminds us, in today’s busy world, not to forget their stories about independence, rugged individualism and family. This uniquely American setting is often seen two-dimensionally in movies and TV shows, but a three-dimensional landscape can be explored and experienced at The Nature Conservancy’s Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Osage County of northeastern Oklahoma.

The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve is big. On a map, it covers an area that is roughly 12 miles wide and 9 miles long! The total acreage is about 40,000 acres, with 25,000 acres reserved for the bison.

This is a wonderful place to visit for many reasons, but one of the most important is seeing this landscape that was almost lost. As the settlers came westward the Bison (also known as American Buffalo) were hunted and the land plowed to create rich and bountiful farmlands. But, there was a high cost. The original population of hundreds of thousands of Bison had been hunted to less than five-hundred individuals and the pristine open prairie that spanned from Texas to Minnesota had been reduced to less than ten percent of the original size. Fortunately, there were visionary folks who saw value in preserving untamed land. Since 1989 the Nature Conservancy, a private, non-profit organization, has restored the largest “fully-functioning portion of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem with the use of about 2500 free-roaming bison.â€

My visit to the tallgrass with my Father started in the town of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, close to the preserve’s southern entrance. The drive down a paved county road was surrounded by woodlands but this soon turned to prairie and the road turned to gravel and then a packed caliche clay.

My visit to the tallgrass with my Father started in the town of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, close to the preserve’s southern entrance. The drive down a paved county road was surrounded by woodlands but this soon turned to prairie and the road turned to gravel and then a packed caliche clay.

Simple signage marked the entrance to the preserve.

The sun this autumn day was shining and the blue sky was punctuated with small white clouds. The wind was blowing about ten miles an hour and the temperature outside was around 40 degrees.

A plaque near the entrance of the preserve includes the text, “The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. You stand at the south edge of the largest unplowed, protected tract which remains of the 142 million acres of tallgrass prairie grasslands that once stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Today, less than ten percent still exists, found mostly in the Flint Hills and Osage Hill regions of Kansas and Oklahoma. In an increasingly crowded and noisy world, what you see is an oasis of space and silence. Here you can experience the same beautiful vistas that greeted the earliest human hunters and gathers many thousands of years ago. This area is indeed a national treasure. Please treat it with respect.â€

A plaque near the entrance of the preserve includes the text, “The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. You stand at the south edge of the largest unplowed, protected tract which remains of the 142 million acres of tallgrass prairie grasslands that once stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Today, less than ten percent still exists, found mostly in the Flint Hills and Osage Hill regions of Kansas and Oklahoma. In an increasingly crowded and noisy world, what you see is an oasis of space and silence. Here you can experience the same beautiful vistas that greeted the earliest human hunters and gathers many thousands of years ago. This area is indeed a national treasure. Please treat it with respect.â€

Sadly, the area surrounding this marker had been marred by a number of empty beer cans left apparently from the evening before. I later learned the roads leading to the preserve are county roads open to the public at all hours. Although there is a cleanup service provided in the preserve by volunteers they cannot be everywhere and at all times. We spent a few minutes picking up the unsightly and very uncool trash.

Twenty minutes or so down the road we stopped at an interpretive marker along the edge of the road. Dark stacked piles of bison poo dotted the area all around us. These were not messy cow patties, rather the dung was tightly packed together into circular disks. These nutrient-rich ‘buffalo chips’ were used by natives and settlers as charcoal because the material burns hot and slow.

Further beyond a few dark bison sentinels stood at the side of hills, these were apparently lone males who had been pushed out from the herds. The mature males, after mating, are no longer needed by the female-dominated herds and are excluded.

Further beyond a few dark bison sentinels stood at the side of hills, these were apparently lone males who had been pushed out from the herds. The mature males, after mating, are no longer needed by the female-dominated herds and are excluded.

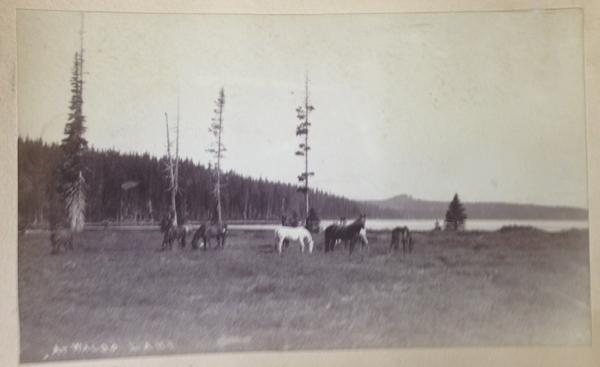

Hawks and kestrels soared over the dry prairie grasses. Most of the birds I saw were sitting on fence posts observing their domain, but sometimes one would fly up, soar overhead and then later swoop down and appeared to have caught a rodent in its sharp talons.

A herd of bison was just ahead. It was easy to see their dark forms against the dry and brown landscape of late autumn. The bison allowed us to slowly drive past. They did not appear to mind us and continued with their business. If they wanted to the bison could cause us some harm as these are great creatures measuring 5-6 feet at the shoulders and 7-10 feet in length. Plus bison can weight up to 2,000 pounds or more! Some of the individuals peered at us through thick, wooly looking coats that would soon protect them from the coming winter cold. We watched them for some time.

A herd of bison was just ahead. It was easy to see their dark forms against the dry and brown landscape of late autumn. The bison allowed us to slowly drive past. They did not appear to mind us and continued with their business. If they wanted to the bison could cause us some harm as these are great creatures measuring 5-6 feet at the shoulders and 7-10 feet in length. Plus bison can weight up to 2,000 pounds or more! Some of the individuals peered at us through thick, wooly looking coats that would soon protect them from the coming winter cold. We watched them for some time.

In the sections of the preserve where we saw fences, the barbed wire included 6 strands and was at least 6 feet tall. We later learned that bison can jump 6 feet laterally and 6 feet in height! The fences are tall so the strands appear at eye-level to intimidate the great beasts from jumping over.

We passed another two groups of bison close to the road. The ‘Bison Loop’ road offered additional miles of great sightseeing.

We passed another two groups of bison close to the road. The ‘Bison Loop’ road offered additional miles of great sightseeing.

The open prairie now presented low canyons of cottonwood trees and ash. In one of these more protected canyons was the Preserve Headquarters. As we pulled into the gravel parking lot an elegant looking eight-point buck darted in front of us and disappeared behind a building.

At the headquarters was an enthusiastic and knowledgeable docent who was a treasure trove of information. One item she mentioned was that the hunting of bison in the 1800s had been so intense that the last wild bison seen in Osage County was in 1869.

The Preserve Headquarters offers a great visitors center. One memorable exhibit showed just how tall the grasses at the tallgrass prairie can grow – as tall as a grown man. The grasses on the tallgrass are very nutritious and part of an amazingly fertile ecosystem. Another item was a table filled with bison bones and fur. I had expected the fur to be harsh feeling but, it was surprisingly soft and extremely warm. A scapula (shoulder blade) was at least 21 inches in length and 14 inches wide – a big bone for a large animal.

The Preserve Headquarters offers a great visitors center. One memorable exhibit showed just how tall the grasses at the tallgrass prairie can grow – as tall as a grown man. The grasses on the tallgrass are very nutritious and part of an amazingly fertile ecosystem. Another item was a table filled with bison bones and fur. I had expected the fur to be harsh feeling but, it was surprisingly soft and extremely warm. A scapula (shoulder blade) was at least 21 inches in length and 14 inches wide – a big bone for a large animal.

Near the headquarters are several short walking trails that looked welcoming, but the temperature that day was lowering and the wind was picking up.

We left the preserve when the sun was very low on the horizon. As the sun lowered past the rolling hills the dark forms of the bison were silhouetted against the rich shades of an ever increasingly dark sky. My heart pumped a little faster and my breathing quickened – it was a scene of the American West.

If you are interested in visiting, make the most of your day, stay overnight in the town on Pawhuska so you can get an early start. There are no gas stations or places to eat on the preserve, so fill up your gas tank in town and take some lunch or munchies with you. Tulsa, Oklahoma, has an airport, but be prepared for a good hour-and-a-half drive just to get to the preserve. Entering the preserve is free, though recommended donations of several dollars per person are welcome at the  headquarters. I was informed by a docent who has been at the preserve for years the best time to visit is in the spring (May) when the wildflowers carpet the landscape and the colors are superb. I plan to return at that time.

headquarters. I was informed by a docent who has been at the preserve for years the best time to visit is in the spring (May) when the wildflowers carpet the landscape and the colors are superb. I plan to return at that time.

Quoted source and learn more:

http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/placesweprotect/tallgrass-prairie-preserve.xml

My visit to the tallgrass with my Father started in the town of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, close to the preserve’s southern entrance. The drive down a paved county road was surrounded by woodlands but this soon turned to prairie and the road turned to gravel and then a packed caliche clay.

My visit to the tallgrass with my Father started in the town of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, close to the preserve’s southern entrance. The drive down a paved county road was surrounded by woodlands but this soon turned to prairie and the road turned to gravel and then a packed caliche clay. A plaque near the entrance of the preserve includes the text, “The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. You stand at the south edge of the largest unplowed, protected tract which remains of the 142 million acres of tallgrass prairie grasslands that once stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Today, less than ten percent still exists, found mostly in the Flint Hills and Osage Hill regions of Kansas and Oklahoma. In an increasingly crowded and noisy world, what you see is an oasis of space and silence. Here you can experience the same beautiful vistas that greeted the earliest human hunters and gathers many thousands of years ago. This area is indeed a national treasure. Please treat it with respect.â€

A plaque near the entrance of the preserve includes the text, “The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. You stand at the south edge of the largest unplowed, protected tract which remains of the 142 million acres of tallgrass prairie grasslands that once stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Today, less than ten percent still exists, found mostly in the Flint Hills and Osage Hill regions of Kansas and Oklahoma. In an increasingly crowded and noisy world, what you see is an oasis of space and silence. Here you can experience the same beautiful vistas that greeted the earliest human hunters and gathers many thousands of years ago. This area is indeed a national treasure. Please treat it with respect.â€ Further beyond a few dark bison sentinels stood at the side of hills, these were apparently lone males who had been pushed out from the herds. The mature males, after mating, are no longer needed by the female-dominated herds and are excluded.

Further beyond a few dark bison sentinels stood at the side of hills, these were apparently lone males who had been pushed out from the herds. The mature males, after mating, are no longer needed by the female-dominated herds and are excluded. A herd of bison was just ahead. It was easy to see their dark forms against the dry and brown landscape of late autumn. The bison allowed us to slowly drive past. They did not appear to mind us and continued with their business. If they wanted to the bison could cause us some harm as these are great creatures measuring 5-6 feet at the shoulders and 7-10 feet in length. Plus bison can weight up to 2,000 pounds or more! Some of the individuals peered at us through thick, wooly looking coats that would soon protect them from the coming winter cold. We watched them for some time.

A herd of bison was just ahead. It was easy to see their dark forms against the dry and brown landscape of late autumn. The bison allowed us to slowly drive past. They did not appear to mind us and continued with their business. If they wanted to the bison could cause us some harm as these are great creatures measuring 5-6 feet at the shoulders and 7-10 feet in length. Plus bison can weight up to 2,000 pounds or more! Some of the individuals peered at us through thick, wooly looking coats that would soon protect them from the coming winter cold. We watched them for some time. We passed another two groups of bison close to the road. The ‘Bison Loop’ road offered additional miles of great sightseeing.

We passed another two groups of bison close to the road. The ‘Bison Loop’ road offered additional miles of great sightseeing. The Preserve Headquarters offers a great visitors center. One memorable exhibit showed just how tall the grasses at the tallgrass prairie can grow – as tall as a grown man. The grasses on the tallgrass are very nutritious and part of an amazingly fertile ecosystem. Another item was a table filled with bison bones and fur. I had expected the fur to be harsh feeling but, it was surprisingly soft and extremely warm. A scapula (shoulder blade) was at least 21 inches in length and 14 inches wide – a big bone for a large animal.

The Preserve Headquarters offers a great visitors center. One memorable exhibit showed just how tall the grasses at the tallgrass prairie can grow – as tall as a grown man. The grasses on the tallgrass are very nutritious and part of an amazingly fertile ecosystem. Another item was a table filled with bison bones and fur. I had expected the fur to be harsh feeling but, it was surprisingly soft and extremely warm. A scapula (shoulder blade) was at least 21 inches in length and 14 inches wide – a big bone for a large animal. headquarters. I was informed by a docent who has been at the preserve for years the best time to visit is in the spring (May) when the wildflowers carpet the landscape and the colors are superb. I plan to return at that time.

headquarters. I was informed by a docent who has been at the preserve for years the best time to visit is in the spring (May) when the wildflowers carpet the landscape and the colors are superb. I plan to return at that time.