The High Cascades in Oregon is beautiful. While much of this chiseled landscape can be viewed at a distance by zipping around in a car, it is best experienced moving at the speed of human – on foot. By hiking, you can appreciate this terrain using all your senses and see it not as entertainment, but as a necessity. Below is an eight-day account of a 100-mile northbound section hike on the PCT from the dry Santiam Pass to the windswept Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood. This hike was powered by a whole-food plant-based (vegan) diet.

Day 1: Santiam Pass to Wasco Lake (10 Miles)

A view of the Santiam Pass trailhead, mile number 2006.9 on the PCT. As my wife and I gathered our gear, we met two sixty-something ladies that started at Crater Lake for a section hike several weeks earlier. These women had already hiked about 175 miles.

A view of the Santiam Pass trailhead, mile number 2006.9 on the PCT. As my wife and I gathered our gear, we met two sixty-something ladies that started at Crater Lake for a section hike several weeks earlier. These women had already hiked about 175 miles.

The weather was beautiful – if a bit warm – that morning. We were joined by two friends, Jack and Cindy, who drove us to the trailhead and then hiked with us for the first five miles of our journey.

The weather was beautiful – if a bit warm – that morning. We were joined by two friends, Jack and Cindy, who drove us to the trailhead and then hiked with us for the first five miles of our journey.

A view of the north side of Three Fingered Jack, a jagged and rugged mountain in the High Cascades that has banded stripes. A PCT thru-hiker stands in the foreground. He was one of about 25 who passed us that day; the oldest being somewhere in her 60s, the youngest about 18, and about half of the thru-hikers were female.

A view of the north side of Three Fingered Jack, a jagged and rugged mountain in the High Cascades that has banded stripes. A PCT thru-hiker stands in the foreground. He was one of about 25 who passed us that day; the oldest being somewhere in her 60s, the youngest about 18, and about half of the thru-hikers were female.

Near the end of our first day, we took a steep side-trail from Minto Pass to Wasco Lake and set up camp. As dusk fell, the sky was pink from a far-away fire. That night elk, frogs, and ducks made noises around our campsite.

Day 2: Wasco Lake to Shale Lake (12 Miles)

A view of Wasco Lake the following morning at about 7 am.

A view of Wasco Lake the following morning at about 7 am.

We enjoyed a mid-morning break on the shores of Rockpile Lake. Several thru-hikers can be seen on the trail at the left. The two women we met a day earlier enjoyed their lunch and a quick swim on the opposite side of the lake.

We enjoyed a mid-morning break on the shores of Rockpile Lake. Several thru-hikers can be seen on the trail at the left. The two women we met a day earlier enjoyed their lunch and a quick swim on the opposite side of the lake.

Much of our day was spent walking through woods that had been burned several years earlier and were now recovering. In the distance, the peak of Mount Jefferson made frequent and teasing appearances.

Much of our day was spent walking through woods that had been burned several years earlier and were now recovering. In the distance, the peak of Mount Jefferson made frequent and teasing appearances.

That evening we camped at Shale Lake and enjoyed an amazing view of the south side of Mount Jefferson. We ate our dinner and watched the evening light blanket the slopes of this iconic High Cascades peak.

That evening we camped at Shale Lake and enjoyed an amazing view of the south side of Mount Jefferson. We ate our dinner and watched the evening light blanket the slopes of this iconic High Cascades peak.

Day 3: Shale Lake to Jefferson Park (12 Miles)

Looking upon a picturesque view of Pamelia Lake from the PCT. This area is a limited entry zone requiring a permit to camp. Our hike that morning was in the forest where we encountered some sizeable old growth trees, and at one point we rounded a corner and surprised a grouse.

Looking upon a picturesque view of Pamelia Lake from the PCT. This area is a limited entry zone requiring a permit to camp. Our hike that morning was in the forest where we encountered some sizeable old growth trees, and at one point we rounded a corner and surprised a grouse.

Milk Creek has cut a 100-foot deep gorge into the slopes of Mount Jefferson. Several backpackers are seen crossing the creek below us.

Milk Creek has cut a 100-foot deep gorge into the slopes of Mount Jefferson. Several backpackers are seen crossing the creek below us.

Overgrown and green, this is what the trail looked like for the rest of the afternoon. It was also humid and hot, making our progress slower than expected. Occasionally, we would see glimpses of Mount Jefferson through the trees.

Overgrown and green, this is what the trail looked like for the rest of the afternoon. It was also humid and hot, making our progress slower than expected. Occasionally, we would see glimpses of Mount Jefferson through the trees.

Russell Creek pours off the mountainside where it meets a “flat†area for about 100 feet before dropping into a deep gorge; this more level area is where the trail crosses. Earlier in the season, the flow can be very strong and this can be a dangerous crossing. Today, though, it just brought about some wet shoes. In this image, a hiker approaches the crossing area. We spoke with her later to find out that she was 18 and was hiking 250 miles of the PCT by herself.

Russell Creek pours off the mountainside where it meets a “flat†area for about 100 feet before dropping into a deep gorge; this more level area is where the trail crosses. Earlier in the season, the flow can be very strong and this can be a dangerous crossing. Today, though, it just brought about some wet shoes. In this image, a hiker approaches the crossing area. We spoke with her later to find out that she was 18 and was hiking 250 miles of the PCT by herself.

In 2016, the Forest Service implemented a new permit system to camp in the stunningly beautiful Jefferson Park area. We did not have a permit and spent a good two hours looking for a walk-up site. The foresters had done an efficient job of decommissioning non-reserved sites; eventually, we found a single site near Russell Lake just as the sun was setting. We were asleep at 9 pm, which is considered “hiker’s midnight.”

Day 4: Jefferson Park to Ollalie Lake (12 Miles)

We enjoyed breakfast under this stunning skyline.

We enjoyed breakfast under this stunning skyline.

The next morning we climbed 1,200 feet out of Jefferson Park. The views were magnificent: wildflowers were in bloom along the trail, and at times it was hard to hear because of the abundance of buzzing coming off nearby flowers.

The next morning we climbed 1,200 feet out of Jefferson Park. The views were magnificent: wildflowers were in bloom along the trail, and at times it was hard to hear because of the abundance of buzzing coming off nearby flowers.

We reached the trail’s summit and could see Mount Hood in the distance. Descending the slope, we passed several snowfields. For several hours our progress was slow going because of the loose rocks, though the trail soon became forested and we passed a number of beautiful mountain lakes.

We reached the trail’s summit and could see Mount Hood in the distance. Descending the slope, we passed several snowfields. For several hours our progress was slow going because of the loose rocks, though the trail soon became forested and we passed a number of beautiful mountain lakes.

Late in the afternoon, we reached Ollalie Lake. Here is a view looking south across the area we just hiked, and in the distance is Mount Jefferson. About two dozen thru-hikers were staying at Ollalie Lake to rest.

Late in the afternoon, we reached Ollalie Lake. Here is a view looking south across the area we just hiked, and in the distance is Mount Jefferson. About two dozen thru-hikers were staying at Ollalie Lake to rest.

We met some new friends at Ollalie Lake:

Darren and Sandy had hiked continuously for 4 months. They were also world travelers that raised geography education awareness by sharing information with students about the places they visit. Their travels can be seen at their site: trekkingtheplanet.net.

Franziska and her family had hiked for 2+ weeks and 100 miles on the PCT, the youngest of her group being her eight-year-old brother! Franziska is the founder of hikeoregon.net.

Ollalie Lake has a small store where my wife and I eagerly purchased a bag of sea salt and vinegar potato chips and promptly devoured the entire bag. At one point there were a whopping total of eight stinky hikers in that little store – ah, the aroma of humanity!

Ollalie Lake has a small store where my wife and I eagerly purchased a bag of sea salt and vinegar potato chips and promptly devoured the entire bag. At one point there were a whopping total of eight stinky hikers in that little store – ah, the aroma of humanity!

Day 5: Ollalie Lake to the Warm Springs Area (14 Miles)

The trail on day five was mostly flat and in the shade of tall trees, making trekking much easier. The forest was drier in this region and water was less abundant than before. When the opportunity presented itself, we filled up our bottles at a small, tranquil trailside spring. The temperature that day was especially warm.

The trail on day five was mostly flat and in the shade of tall trees, making trekking much easier. The forest was drier in this region and water was less abundant than before. When the opportunity presented itself, we filled up our bottles at a small, tranquil trailside spring. The temperature that day was especially warm.

We arrived at Trooper Springs near the Lemiti Marsh area. This was our last water for about twelve miles. The spring was a welcome site although a small and precarious platform needed repair. We were attacked by horseflies; they were numerous, aggressive, and very persistent. Needless to say, we did not stay long.

We arrived at Trooper Springs near the Lemiti Marsh area. This was our last water for about twelve miles. The spring was a welcome site although a small and precarious platform needed repair. We were attacked by horseflies; they were numerous, aggressive, and very persistent. Needless to say, we did not stay long.

Taking care of some much-needed laundry at the spring using the “Ziplock spin cycle” washing method.

Taking care of some much-needed laundry at the spring using the “Ziplock spin cycle” washing method.

Walking through a clearcut was a stark contrast to the lush forest we had seen all day. Near this area, we found the strangest price of trash on the trip: a Howard Johnson’s hotel key card lying next to the trail. We picked it up.

Walking through a clearcut was a stark contrast to the lush forest we had seen all day. Near this area, we found the strangest price of trash on the trip: a Howard Johnson’s hotel key card lying next to the trail. We picked it up.

We located a bare spot at the edge of the trail and camped for the night. Trailside camping can look messy, but everything goes back into the pack and we always leave the site cleaner than we found it.

We located a bare spot at the edge of the trail and camped for the night. Trailside camping can look messy, but everything goes back into the pack and we always leave the site cleaner than we found it.

Day 6: Warm Springs Area to Timothy Lake (18 Miles)

We were up early that morning to hike six miles to the next water at the Warm Springs River.

Shown is an old style PCT trail marker that we found, one of the few older versions that we saw on the entire trip.

Shown is an old style PCT trail marker that we found, one of the few older versions that we saw on the entire trip.

Crossing the Warm Springs River. It was more a small creek at this point, but the water the clean and cold – a welcome site.

Crossing the Warm Springs River. It was more a small creek at this point, but the water the clean and cold – a welcome site.

As I took off my shoes I realized just how dusty the trail was that day.

As I took off my shoes I realized just how dusty the trail was that day.

That evening we stealth camped near the trail close to Timothy Lake. During the night we unzipped the tent for a “nature break” – only to be scolded by an owl that repeatedly whooo’d at us until we went back to bed.

That evening we stealth camped near the trail close to Timothy Lake. During the night we unzipped the tent for a “nature break” – only to be scolded by an owl that repeatedly whooo’d at us until we went back to bed.

Day 7: Timothy Lake to Frog Lake (11 Miles)

The next morning was slow; we woke up late, and it seemed to take forever to get moving. We found a quiet site on the shoreline of Timothy Lake to we rest, take care of some laundry, and enjoy the sun for a couple of hours before continuing.

Several miles down the trail was Crater Creek, a beautiful riparian area with some astonishingly cold water: a welcome find on a hot day. We soaked our feet, took a twenty-second dip (the water was that frigid), then soaked our shirts and put them on as a natural air-conditioner. We made a stop at Little Crater Lake, the source of the creek. Little Crater Lake is astonishingly blue like it’s larger cousin, but this was not volcanic in origin. Rather, this was a large artesian well. Continuing down the trail, we passed a gravel forest service road and found a bag hanging on PCT post. Inside were some small apples or Asian pears – some unexpected trail magic in the middle of nowhere.

Several miles down the trail was Crater Creek, a beautiful riparian area with some astonishingly cold water: a welcome find on a hot day. We soaked our feet, took a twenty-second dip (the water was that frigid), then soaked our shirts and put them on as a natural air-conditioner. We made a stop at Little Crater Lake, the source of the creek. Little Crater Lake is astonishingly blue like it’s larger cousin, but this was not volcanic in origin. Rather, this was a large artesian well. Continuing down the trail, we passed a gravel forest service road and found a bag hanging on PCT post. Inside were some small apples or Asian pears – some unexpected trail magic in the middle of nowhere.

This was our first view of Mount Hood after about 40 miles of hiking – what a fantastic sight.

This was our first view of Mount Hood after about 40 miles of hiking – what a fantastic sight.

We took a side trail to Frog Lake for some water where there was a hand pump that drew water from a well. As we entered the campground we were momentary celebrities answering questions like: “Where did you hike from?†“How many days have you been out?†“Tell me about your gear?†etc. It was an odd but welcome feeling. That night, we camped just outside the campground on a forest road.

We took a side trail to Frog Lake for some water where there was a hand pump that drew water from a well. As we entered the campground we were momentary celebrities answering questions like: “Where did you hike from?†“How many days have you been out?†“Tell me about your gear?†etc. It was an odd but welcome feeling. That night, we camped just outside the campground on a forest road.

Day 8: Frog Lake to Timberline Lodge (11 Miles)

The next morning, we stopped back in at the campground for some water and said goodbye to our new fans. A girl pulled up on her bike. “Good luck!†she exclaimed, and even a “Thanks for being so inspiring” from an adult. It felt good to hear, but the truly inspirational folks were the PCT thru-hikers who had hiked 2,663 miles and spent six months on the trail.

We made good time that day ascending Mount Hood: 5.5 miles in two hours with a significant elevation gain; we were getting our hiking legs.

Finally, the green of the trees turned to open space and vistas as we passed the timberline. It was windy with twenty to thirty mile an hour gusts that kicked up sand and dust. We wore our sunglasses to keep volcanic grit out of our eyes.

Finally, the green of the trees turned to open space and vistas as we passed the timberline. It was windy with twenty to thirty mile an hour gusts that kicked up sand and dust. We wore our sunglasses to keep volcanic grit out of our eyes.

There was an abundance of mountain flowers on the trail.

There was an abundance of mountain flowers on the trail.

Close to the Timberline Lodge, the views were fantastic! We could see much of the route that we had spent the past week traversing.

Close to the Timberline Lodge, the views were fantastic! We could see much of the route that we had spent the past week traversing.

We arrived at the Timberline Lodge, mile 2107.3 on the PCT, and 100 miles from our starting point at Santiam Pass. Inside the lodge, scores of thru-hikers had taken refuge in the common areas. There was access to food and good company, with couches for sleeping and a warm fire to enjoy in the evening. We met some new friends here: Shepherd, Snow, Lonestar, and Patch, all thru-hikers who started at the Mexican border and were resting before their final push into Washington State and Canada.

We arrived at the Timberline Lodge, mile 2107.3 on the PCT, and 100 miles from our starting point at Santiam Pass. Inside the lodge, scores of thru-hikers had taken refuge in the common areas. There was access to food and good company, with couches for sleeping and a warm fire to enjoy in the evening. We met some new friends here: Shepherd, Snow, Lonestar, and Patch, all thru-hikers who started at the Mexican border and were resting before their final push into Washington State and Canada.

Looking through the door at the Timberline Lodge onto the Roosevelt Terrace: in the distance Jefferson Peak, and behind it, Three Fingered Jack and Santiam Pass. From the lodge, we were able to take public transit back home.

Looking through the door at the Timberline Lodge onto the Roosevelt Terrace: in the distance Jefferson Peak, and behind it, Three Fingered Jack and Santiam Pass. From the lodge, we were able to take public transit back home.

On the way, we encountered several snowfields, one of which was very steep, but the stunning views from the top were well worth the extra effort in getting there. In the distance, Mount Scott was enticingly clear of snow, though we later learned it was impossible to reach because several miles of the eastern rim highway was closed for repairs. Returning down the mountainside we visited the small loop trail of Godfrey Glen where we collected trash that uncaring visitors had left. We collected enough garbage to fill a large bag! That evening we sat around the campfire and commented on the number of stars that were visible, where was the rain? All was calm until 2 am when the rain arrived and temperatures lowered to just above freezing. Our two members in their “good deal†tent had a cold and wet night.

On the way, we encountered several snowfields, one of which was very steep, but the stunning views from the top were well worth the extra effort in getting there. In the distance, Mount Scott was enticingly clear of snow, though we later learned it was impossible to reach because several miles of the eastern rim highway was closed for repairs. Returning down the mountainside we visited the small loop trail of Godfrey Glen where we collected trash that uncaring visitors had left. We collected enough garbage to fill a large bag! That evening we sat around the campfire and commented on the number of stars that were visible, where was the rain? All was calm until 2 am when the rain arrived and temperatures lowered to just above freezing. Our two members in their “good deal†tent had a cold and wet night. We explored the Visitor’s Center, the Sinnott Memorial Overlook (featuring an indoor exhibit room) and the gift shop to escape the fog, wind, rain, and occasional snow flurries. The fog was so thick we could not see the lake or a few hundred feet in front of us. In the afternoon we moved below the cloud line to hike the picturesque Annie Creek trail. Although a short hike, it was very picturesque. Laurie and Brad had reservations at the Crater Lake Lodge for dinner, they generously increased their table size to include all of us so we could get out of the rain and have some warm food. About 8 pm that evening the sky cleared and at first, the temperatures seemed warm. The group campfire that evening had just half of the group, the remainder had gone to bed early. The two members in the “good deal†tent had another cold and memorable night. In the middle of the night I awoke and was stunned by the visibility of the night sky – there were thousands of stars! My tent thermometer showed that temperatures had dropped into the upper twenties.

We explored the Visitor’s Center, the Sinnott Memorial Overlook (featuring an indoor exhibit room) and the gift shop to escape the fog, wind, rain, and occasional snow flurries. The fog was so thick we could not see the lake or a few hundred feet in front of us. In the afternoon we moved below the cloud line to hike the picturesque Annie Creek trail. Although a short hike, it was very picturesque. Laurie and Brad had reservations at the Crater Lake Lodge for dinner, they generously increased their table size to include all of us so we could get out of the rain and have some warm food. About 8 pm that evening the sky cleared and at first, the temperatures seemed warm. The group campfire that evening had just half of the group, the remainder had gone to bed early. The two members in the “good deal†tent had another cold and memorable night. In the middle of the night I awoke and was stunned by the visibility of the night sky – there were thousands of stars! My tent thermometer showed that temperatures had dropped into the upper twenties. We parked at a junction and walked down an old logging road that was being reclaimed by the forest. Then we disappeared into the bushes, venturing down an elk trail. Posted on a tree was a sign that told us this was not the path to the Devil’s Staircase waterfall and unless you’re prepared to stay the night, and have Search and Rescue to look for you, to turn back. Fortunately, we had a guide for our inaugural visit.

We parked at a junction and walked down an old logging road that was being reclaimed by the forest. Then we disappeared into the bushes, venturing down an elk trail. Posted on a tree was a sign that told us this was not the path to the Devil’s Staircase waterfall and unless you’re prepared to stay the night, and have Search and Rescue to look for you, to turn back. Fortunately, we had a guide for our inaugural visit. A forest of Salmonberries obstructed our path, so we made a trail straight up a ridge, then down into a forest of sword ferns. The ferns stood at five to six feet in height, so they engulfed us all and many of the shorter members traveled with their arms raised straight overhead. These tranquil glens often hid downed logs and it was easy to twist ankles or slam shins.

A forest of Salmonberries obstructed our path, so we made a trail straight up a ridge, then down into a forest of sword ferns. The ferns stood at five to six feet in height, so they engulfed us all and many of the shorter members traveled with their arms raised straight overhead. These tranquil glens often hid downed logs and it was easy to twist ankles or slam shins. A fallen giant became our catwalk above the salmonberries, foxgloves, and ferns. We crossed a creek, but could barely see the water because of the thick undergrowth. Scampering down the side of the massive tree, we squatted and crawled through a small jungle, then emerged at the root base of the fallen giant – it was 25 feet tall!

A fallen giant became our catwalk above the salmonberries, foxgloves, and ferns. We crossed a creek, but could barely see the water because of the thick undergrowth. Scampering down the side of the massive tree, we squatted and crawled through a small jungle, then emerged at the root base of the fallen giant – it was 25 feet tall! In front of us was the Dark Grove, a cathedral of 8-foot wide Douglas Fir trees. The trees were dark in appearance, the result of fire about 150 years earlier. Touching the bark a charcoal residue was imprinted on fingers. The tree model is Becky Lipton.

In front of us was the Dark Grove, a cathedral of 8-foot wide Douglas Fir trees. The trees were dark in appearance, the result of fire about 150 years earlier. Touching the bark a charcoal residue was imprinted on fingers. The tree model is Becky Lipton. Crossing back across the fallen giant, we stood at the base of one of the largest trees we saw that day. Eight people stood at its base, arms outstretched and hands grasped. They counted one, two, three… their calls became muffled as they rounded the opposite side…the voices returned and the loop stopped – at seven and a half people! This immense tree was somewhere between 35 to 40 feet in circumference! Several hikers mentioned they felt like kids in a giant outdoor playground.

Crossing back across the fallen giant, we stood at the base of one of the largest trees we saw that day. Eight people stood at its base, arms outstretched and hands grasped. They counted one, two, three… their calls became muffled as they rounded the opposite side…the voices returned and the loop stopped – at seven and a half people! This immense tree was somewhere between 35 to 40 feet in circumference! Several hikers mentioned they felt like kids in a giant outdoor playground.

The Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon is breathtakingly beautiful. This diverse landscape of volcanoes, snow, forests, creeks, lava fields, and lakes gives hikers the opportunity to explore a vibrant topography. The wilderness encompasses 281,190-acres and is dominated by three volcanic peaks: North, Middle, and South, that each exceeds 10,000-feet in height! Several paved roads around the perimeter of the wilderness allow visitors to see vistas with just a car ride, but to really appreciate the immensity of this setting some footwork is required. Here are some pictures of a 34-mile, 4-day trip along the north and eastern portions of the wilderness ending between Middle and South Sister at a subalpine area known as Camp Lake.

The Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon is breathtakingly beautiful. This diverse landscape of volcanoes, snow, forests, creeks, lava fields, and lakes gives hikers the opportunity to explore a vibrant topography. The wilderness encompasses 281,190-acres and is dominated by three volcanic peaks: North, Middle, and South, that each exceeds 10,000-feet in height! Several paved roads around the perimeter of the wilderness allow visitors to see vistas with just a car ride, but to really appreciate the immensity of this setting some footwork is required. Here are some pictures of a 34-mile, 4-day trip along the north and eastern portions of the wilderness ending between Middle and South Sister at a subalpine area known as Camp Lake. My wife and I began our first day with a late start; we hiked 3 miles south from the Lava Camp trailhead and spent the night at South Matthieu Lake. Smoke from forest fires in the region made everything, even a view of North Sister and the moon, opaque. That night, an anticipated cool breeze was replaced by a warm wind that blew in from high plains of Oregon where a large ground fire was burning. In the middle of the night, the smoke became extremely thick and breathing for several hours was difficult. By morning the winds had shifted and the air was clearer.

My wife and I began our first day with a late start; we hiked 3 miles south from the Lava Camp trailhead and spent the night at South Matthieu Lake. Smoke from forest fires in the region made everything, even a view of North Sister and the moon, opaque. That night, an anticipated cool breeze was replaced by a warm wind that blew in from high plains of Oregon where a large ground fire was burning. In the middle of the night, the smoke became extremely thick and breathing for several hours was difficult. By morning the winds had shifted and the air was clearer. The next day we hiked 14 miles; 7 of which reminded us just how destructive forest fires can be, constantly around us were the stark and charcoaled remains of incinerated trees. This conflagration was called the Pole Creek Fire and occurred just 3 years ago in 2012.

The next day we hiked 14 miles; 7 of which reminded us just how destructive forest fires can be, constantly around us were the stark and charcoaled remains of incinerated trees. This conflagration was called the Pole Creek Fire and occurred just 3 years ago in 2012. Several small creeks crossed our path, most were dry, but Alder Creek’s water was cold and clear even though the flow was very low. The creek offered a respite from a temperature of 85 degrees and hot sun that was beating down. We welcomed the opportunity for rest and refill our water bottles at this little pool.

Several small creeks crossed our path, most were dry, but Alder Creek’s water was cold and clear even though the flow was very low. The creek offered a respite from a temperature of 85 degrees and hot sun that was beating down. We welcomed the opportunity for rest and refill our water bottles at this little pool. The North Sister towers in the distance. Continuing south the trail crossed several areas where the fire had not reached; these were often pumice expanses where vegetation was dispersed.

The North Sister towers in the distance. Continuing south the trail crossed several areas where the fire had not reached; these were often pumice expanses where vegetation was dispersed. As we crossed Soap Creek we saw a number Bumble Bees buzzing from one flower to another. Soap Creek gets its name from the soapy color of the water; this is because of the sediment that gets carried down in the glacial meltwater.

As we crossed Soap Creek we saw a number Bumble Bees buzzing from one flower to another. Soap Creek gets its name from the soapy color of the water; this is because of the sediment that gets carried down in the glacial meltwater. The trail turned to the west and the terrain gradually increased in elevation. After about an hour and a half we crossed the North Fork of Whychus Creek, which had to be traversed via several logs that served as a makeshift bridge, below us the grey and auburn glacial melt water loudly churned. Its source was about 2 miles upstream at the Hayden and Diller Glaciers. After crossing the views opened up.

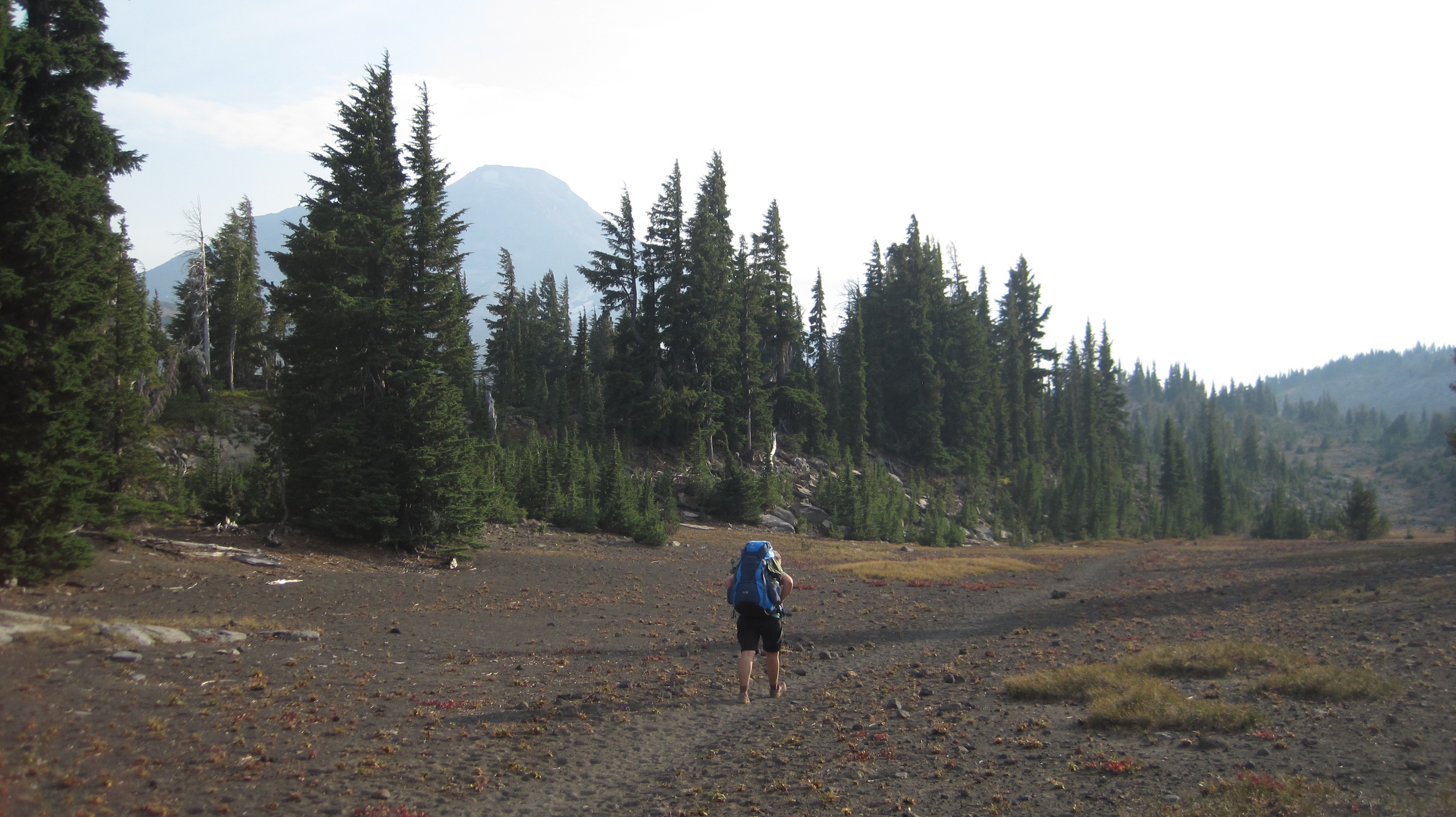

The trail turned to the west and the terrain gradually increased in elevation. After about an hour and a half we crossed the North Fork of Whychus Creek, which had to be traversed via several logs that served as a makeshift bridge, below us the grey and auburn glacial melt water loudly churned. Its source was about 2 miles upstream at the Hayden and Diller Glaciers. After crossing the views opened up. A photo of Christiane hiking through a pumice area on our way to Camp Lake; walking on this material is akin to walking on dry sand.

A photo of Christiane hiking through a pumice area on our way to Camp Lake; walking on this material is akin to walking on dry sand. What a beautiful landscape!

What a beautiful landscape! A view of South Sister on the horizon; this dramatic peak is 10,358-feet in elevation!

A view of South Sister on the horizon; this dramatic peak is 10,358-feet in elevation! Our destination for the night, Camp Lake at 6,952-feet. The wind here can be unrelenting, this is because the lake’s location is sandwiched in a pass between Middle and South Sister. The wind was strong that afternoon so we found sanctuary behind a glacial moraine and set up camp.

Our destination for the night, Camp Lake at 6,952-feet. The wind here can be unrelenting, this is because the lake’s location is sandwiched in a pass between Middle and South Sister. The wind was strong that afternoon so we found sanctuary behind a glacial moraine and set up camp. Our original plan was to stay the night at Camp Lake and then in the morning continue over the pass. This would have included: hiking up a climber’s trail for an hour and up several hundred feet in elevation, crossing over a snowfield and down the western side of the mountain and to several remote lakes then overland another 3 miles to the Pacific Crest Trail. But, uncertain weather changed our plans. The forecast had called for a rainstorm along with high winds within the next 24 hours and we were hoping to make it over the pass before the rain. That evening dark clouds marched across the sky. As the sun disappeared under the horizon the temperature dropped well into the 40s and that night we heard several deep and rumbling crashes of thunder. The wind howled into the morning and for several hours we heard rain outside and at times our tent was pelted by ice.

Our original plan was to stay the night at Camp Lake and then in the morning continue over the pass. This would have included: hiking up a climber’s trail for an hour and up several hundred feet in elevation, crossing over a snowfield and down the western side of the mountain and to several remote lakes then overland another 3 miles to the Pacific Crest Trail. But, uncertain weather changed our plans. The forecast had called for a rainstorm along with high winds within the next 24 hours and we were hoping to make it over the pass before the rain. That evening dark clouds marched across the sky. As the sun disappeared under the horizon the temperature dropped well into the 40s and that night we heard several deep and rumbling crashes of thunder. The wind howled into the morning and for several hours we heard rain outside and at times our tent was pelted by ice. When we woke, the sky was grey in color but appeared mostly calm, though as I stepped out from behind the shelter of the moraine the wind almost knocked me over. I collected water at the lake and was surprised at how chilled I had become in just a few minutes; the wind was deceptively cold. Partially frozen raindrops fell sporadically. My wife and I made the decision to hold off crossing over the pass during this trip. We would return by the route we came.

When we woke, the sky was grey in color but appeared mostly calm, though as I stepped out from behind the shelter of the moraine the wind almost knocked me over. I collected water at the lake and was surprised at how chilled I had become in just a few minutes; the wind was deceptively cold. Partially frozen raindrops fell sporadically. My wife and I made the decision to hold off crossing over the pass during this trip. We would return by the route we came. The area’s starkness was beautiful. Several tents were dotted around the area, all of them, like the tent, is shown in the photo, was strategically placed behind natural wind brakes.

The area’s starkness was beautiful. Several tents were dotted around the area, all of them, like the tent, is shown in the photo, was strategically placed behind natural wind brakes. Our hike off the mountain was cold and occasionally it rained on us. At about noon the sun briefly came out, but this did not last long for the sky again turned dark and overcast. We hiked out of the burn zone and returned to the Matthieu Lakes area about dinnertime. That evening, the weather was peaceable, but about 7 pm the wind started up, by 8 pm it roared through camp with gusts reaching 40-50 miles an hour, by 9 pm the rain started. This continued into dawn. We slept comfortably in our tent.

Our hike off the mountain was cold and occasionally it rained on us. At about noon the sun briefly came out, but this did not last long for the sky again turned dark and overcast. We hiked out of the burn zone and returned to the Matthieu Lakes area about dinnertime. That evening, the weather was peaceable, but about 7 pm the wind started up, by 8 pm it roared through camp with gusts reaching 40-50 miles an hour, by 9 pm the rain started. This continued into dawn. We slept comfortably in our tent. The next morning was drippy and low clouds blew over the treetops. Later that morning we hiked out the last 3 miles. As we approached the Lava Camp trailhead the sky offered us some brief patches of blue. We ended our day with each other clinking together mugs of trail coffee in honor of a good trip.

The next morning was drippy and low clouds blew over the treetops. Later that morning we hiked out the last 3 miles. As we approached the Lava Camp trailhead the sky offered us some brief patches of blue. We ended our day with each other clinking together mugs of trail coffee in honor of a good trip.

Waldo Lake is one of Oregon’s largest bodies of water, though its lack of amenities such as convenience stores, resorts, and ban of motorized motors upon the water makes this destination easily overlooked. If you’re interested in a great overnight backpacking trip to try the Jim Weaver Loop, a 20.2-mile trail around Waldo lake, here are some photos taken in early July.

Waldo Lake is one of Oregon’s largest bodies of water, though its lack of amenities such as convenience stores, resorts, and ban of motorized motors upon the water makes this destination easily overlooked. If you’re interested in a great overnight backpacking trip to try the Jim Weaver Loop, a 20.2-mile trail around Waldo lake, here are some photos taken in early July. Near Mile 2. Our first stop was at the South Waldo shelter, it was fully equipped with wood and a stove; this is a popular destination in the winter. We continued on.

Near Mile 2. Our first stop was at the South Waldo shelter, it was fully equipped with wood and a stove; this is a popular destination in the winter. We continued on. The south shore had some great views of the South and Middle Sisters. The trail now meandered up the western side of the lake.

The south shore had some great views of the South and Middle Sisters. The trail now meandered up the western side of the lake. Cascade Blueberry

Cascade Blueberry Close to Mile 5. Overlooking the picturesque Klovdahl Bay. Overhead, the clouds began building into thunderheads; in the distance, we could hear the rumbling crescendo of thunder as though gigantic timpani drums were being struck.

Close to Mile 5. Overlooking the picturesque Klovdahl Bay. Overhead, the clouds began building into thunderheads; in the distance, we could hear the rumbling crescendo of thunder as though gigantic timpani drums were being struck. The western trail has a number of places where the forest looks like it had a close encounter with a forest fire; note the scoring on the tree at the right.

The western trail has a number of places where the forest looks like it had a close encounter with a forest fire; note the scoring on the tree at the right. Mile 10. Continuing north. Seen in the right on the image, about 2-miles away is a scarred hilltop within the burn zone.

Mile 10. Continuing north. Seen in the right on the image, about 2-miles away is a scarred hilltop within the burn zone. We spied several campsites peppered along the western shore of the lake, but as we reached the northern shore we discovered a favorite spot was vacant. As evening approached we appreciated a gentle breeze that chased most of the mosquitoes away.

We spied several campsites peppered along the western shore of the lake, but as we reached the northern shore we discovered a favorite spot was vacant. As evening approached we appreciated a gentle breeze that chased most of the mosquitoes away. Enjoying a gorgeous sunset. The sky was clear that night when the stars came out they were so bright you could almost touch them.

Enjoying a gorgeous sunset. The sky was clear that night when the stars came out they were so bright you could almost touch them. A very small toad had made its home just outside our tent during the night. It was discovered in the morning hiding next to one of our shoes.

A very small toad had made its home just outside our tent during the night. It was discovered in the morning hiding next to one of our shoes. Roughly Mile 12. Heading east, the trail meanders through the burn zone along the north shore. This day was going to be hot so we tried to cross before the sun rose too high in the sky. Several weeks earlier, during

Roughly Mile 12. Heading east, the trail meanders through the burn zone along the north shore. This day was going to be hot so we tried to cross before the sun rose too high in the sky. Several weeks earlier, during  Mile 13-ish. Standing on the north shore looking across to the southern shore. The morning was calm, it was difficult to tell where the sky ended and the lake began. Determining the depth of the logs seen the water was difficult, but if the terrain continued its steep angle into the water, these logs were at least 40 feet deep in the foreground and 60+ feet deep further out.

Mile 13-ish. Standing on the north shore looking across to the southern shore. The morning was calm, it was difficult to tell where the sky ended and the lake began. Determining the depth of the logs seen the water was difficult, but if the terrain continued its steep angle into the water, these logs were at least 40 feet deep in the foreground and 60+ feet deep further out. A Couple Selfie taken on the trail within the burn zone.

A Couple Selfie taken on the trail within the burn zone. We’re out of the burn zone and heading south along the eastern edge of the lake. Half of the trail around Waldo Lake is in the woods, with only brief glimpses of the water. Be prepared to see lots of trees.

We’re out of the burn zone and heading south along the eastern edge of the lake. Half of the trail around Waldo Lake is in the woods, with only brief glimpses of the water. Be prepared to see lots of trees. Just as we neared the south shore a massive toad was seen at the edge of the trail eating mosquitoes. During the entire trip, mosquitoes were not a big issue, though the last several miles of the trail we were devoured by these little flying beasts! I was glad to see this toad!

Just as we neared the south shore a massive toad was seen at the edge of the trail eating mosquitoes. During the entire trip, mosquitoes were not a big issue, though the last several miles of the trail we were devoured by these little flying beasts! I was glad to see this toad! Mile 20.2. The best part of finishing the loop trail around Waldo Lake is that you can dip your feet into the lake’s cold and clean water.

Mile 20.2. The best part of finishing the loop trail around Waldo Lake is that you can dip your feet into the lake’s cold and clean water.

Approaching Wizard Island, even several miles away, is very impressive.

Approaching Wizard Island, even several miles away, is very impressive. As the boat approaches Wizard Island the size and grandeur of this volcanic cone become apparent.

As the boat approaches Wizard Island the size and grandeur of this volcanic cone become apparent. Hiking to the top of Wizard Island the trail climbs 760 feet, but this is nothing compared to the eastern rim of the crater which towers above me. In the photo, the Watchman scrapes the sky at 1840 feet above the lake’s surface. Seen between the trees, on the water (crossing Skell Channel) is a small white line, this is one of the boats that transport passengers to the island.

Hiking to the top of Wizard Island the trail climbs 760 feet, but this is nothing compared to the eastern rim of the crater which towers above me. In the photo, the Watchman scrapes the sky at 1840 feet above the lake’s surface. Seen between the trees, on the water (crossing Skell Channel) is a small white line, this is one of the boats that transport passengers to the island. The views hiking to the top of Wizard Island are jaw-dropping.

The views hiking to the top of Wizard Island are jaw-dropping. Think of Wizard Island as a small volcano, and it has a crater; this picture shows several people hiking out. The rim of Crater Lake looms on the horizon.

Think of Wizard Island as a small volcano, and it has a crater; this picture shows several people hiking out. The rim of Crater Lake looms on the horizon. This Ground Squirrel is a resident of Wizard Island. He was demanding a food tithe from me for visiting his island retreat.

This Ground Squirrel is a resident of Wizard Island. He was demanding a food tithe from me for visiting his island retreat. A view from atop Wizard Island looking across Crater Lake to the opposite rim which is about 5 miles away. The blue color is just magnificent.

A view from atop Wizard Island looking across Crater Lake to the opposite rim which is about 5 miles away. The blue color is just magnificent. Hiking down the cinder cone we enjoy a rich tapestry of colors – a masterpiece painted by nature!

Hiking down the cinder cone we enjoy a rich tapestry of colors – a masterpiece painted by nature! This is one of the few boats allowed on Crater Lake. It is seen here delivering visitors; this boat will take us on our return trip around the lake’s perimeter in a counterclockwise direction. Our next stop was the southern shore to see a slide area and the Phantom Ship.

This is one of the few boats allowed on Crater Lake. It is seen here delivering visitors; this boat will take us on our return trip around the lake’s perimeter in a counterclockwise direction. Our next stop was the southern shore to see a slide area and the Phantom Ship. The spires of the Phantom Ship, an island in the lake, which under low-light conditions resembles a ghost ship.

The spires of the Phantom Ship, an island in the lake, which under low-light conditions resembles a ghost ship. Looking into the water from the edge of the boat we saw this dramatic difference in color. The interpreter on the boat said the contrast was because we were passing over an underwater ledge, to the left the water depth was about 900 feet, to the right the depths plunged to 1,600 feet!

Looking into the water from the edge of the boat we saw this dramatic difference in color. The interpreter on the boat said the contrast was because we were passing over an underwater ledge, to the left the water depth was about 900 feet, to the right the depths plunged to 1,600 feet! Crater Lake’s legendary “blue” water.

Crater Lake’s legendary “blue” water.

In the spring and summer of 2014, I enjoyed volunteering with the Nature Conservancy of Oregon (Southwest office). My role was to help grow participation in the local volunteering community. My services included upgrading their email management tool (to Constant Contact) and designing several newsletters.

In the spring and summer of 2014, I enjoyed volunteering with the Nature Conservancy of Oregon (Southwest office). My role was to help grow participation in the local volunteering community. My services included upgrading their email management tool (to Constant Contact) and designing several newsletters.